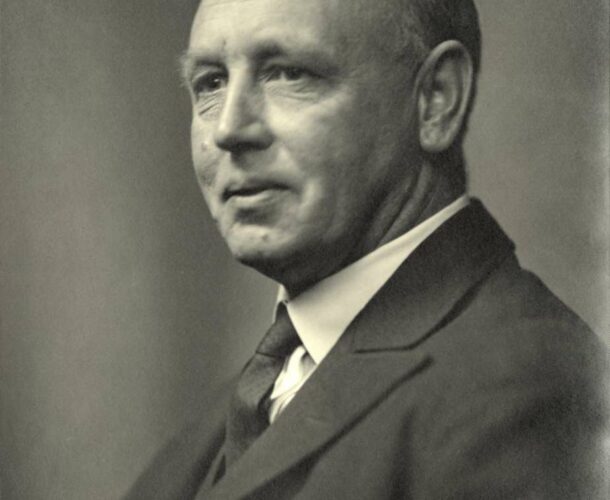

Dr Charles Kellaway becomes the institute’s second director (1923-44), raising the institute’s public profile and successfully steering it through the Great Depression.

His early priority is to establish new sources of funding to supplement the income provided by the Walter and Eliza Hall Trust. His efforts result in the first direct funding for medical research from the Commonwealth Government, paving the way for the establishment of the National Health and Medical Research Council.

With the outbreak of World War II he shifts the institute’s research focus to include infectious agents affecting Australian soldiers in the tropics.

Kellaway: to the laboratory via the battlefield

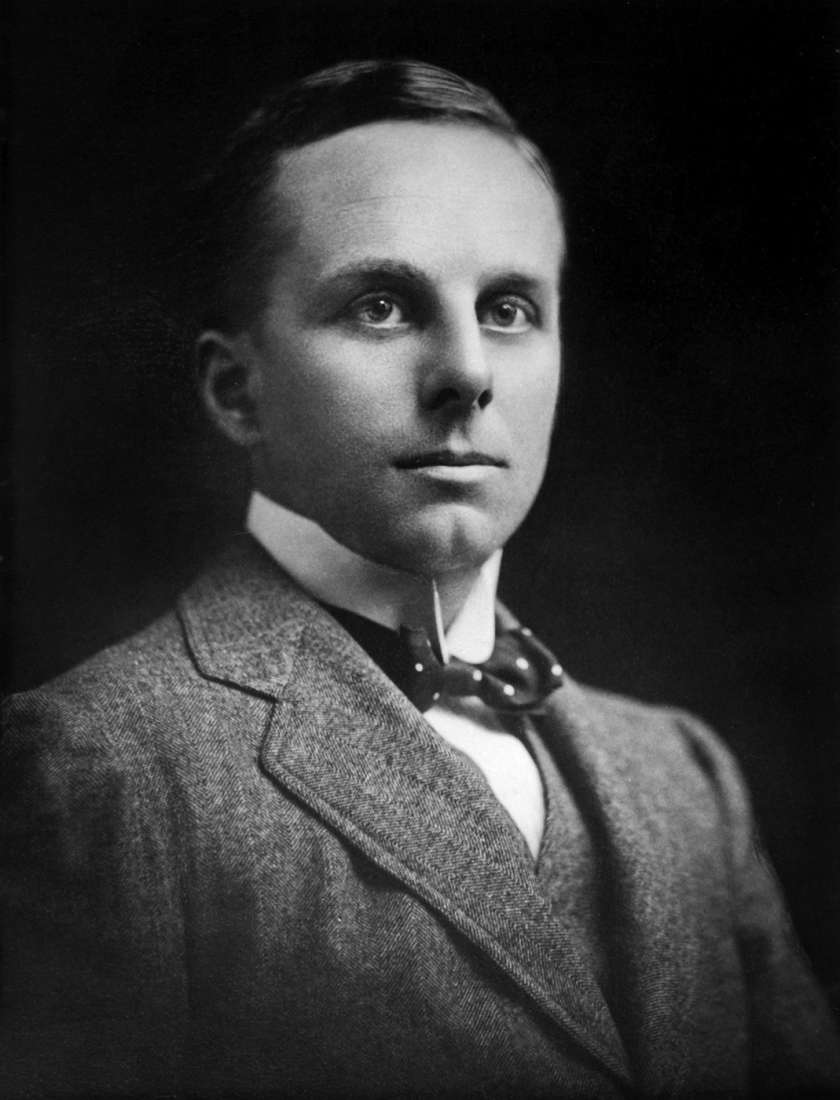

Charles Kellaway, son of a clergyman, grew up in country Victoria and dreamed of becoming a medical missionary in Egypt. Fate, in the form of World War I intervened.

Considered the most brilliant medical graduate yet to emerge from the University of Melbourne, he enlisted once his postgraduate studies were completed, arriving in the Middle East just after the evacuation of Gallipoli.

What he witnessed on the battlefield shattered his faith in God. But the man who steered the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute through an otherwise crippling period never lost faith in the power of medicine to better humanity.

His qualities of personal sacrifice and grace under fire were immediately evident. In 1917 he joined the Australian Imperial Force in France as regimental medical officer for the 13th Battalion. His fortitude during a battle at Zonnebeke earned him a Military Cross.

“During the 24 hours following the attack,” Kellaway’s commanding officer noted, “he worked without a moment’s respite, dealing with the wounded of five battalions in addition to his own, and at the same time controlling the work of his Stretcher Bearers.”

Research in England

Kellaway’s service in France ended soon after his younger brother vanished during an artillery barrage at Passchendaele, his remains never found. A shattered Kellaway went to London for convalescence. During this time he was seconded to the Australian Flying Corps, which led him to undertake studies on the problems of oxygen depletion in aircrew flying at high altitudes.

This work at the newly formed National Institute for Medical Research led Kellaway to form a lifelong association with the English pharmacologist and physiologist (Sir) Henry Dale. When Kellaway was appointed a Foulerton scholar of the Royal Society after the war, he and Dale investigated the nature of anaphylaxis, a potentially life-threatening allergic reaction, and this set the direction of Kellaway’s subsequent research.

Research achievements at the institute

In 1923, aged 34, Kellaway returned from London to take over as the second director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

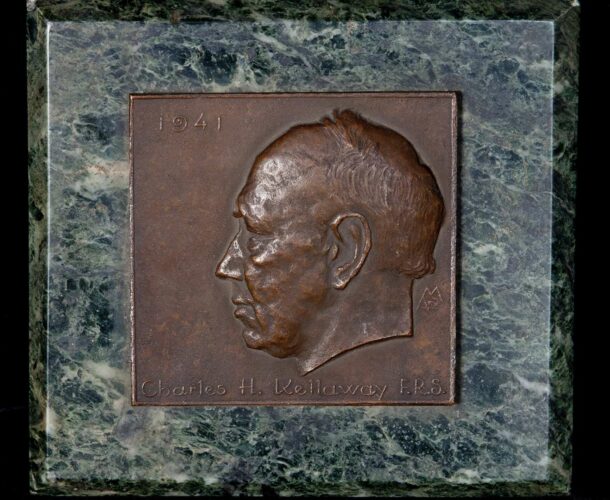

In the lab he applied the techniques he had learned in London to analyse the pharmacology of snake venoms. His international reputation was sealed with his “masterly” work with Neil Hamilton Fairley on snakebite eventually leading to his 1940 Fellowship of the Royal Society. The work led to a collaboration with the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories to manufacture tiger snake antivenom —the first to enter clinical use in Australia. It was put to good use when a snake Kellaway had been milking bit him.

Towards the end of the 1930s, he began to use venoms as a tool to investigate tissue damage. His most profound contribution to experimental physiology is his discovery, along with Everton Trethewie and Wilhelm Feldberg, of the liberation of “slow reacting substance” of anaphylaxis that caused a prolonged contraction of smooth muscle. Fifty years later this work founded new discoveries in asthma treatment.

Leadership and administration

But Kellaway’s research was ultimately sacrificed for his administrative duties. When he took over as director, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute was little more than a set of clinical laboratories attached to the then Melbourne Hospital, with fewer than a dozen staff and a paltry annual budget of £2500. He soon acquired a cadre of aspiring scientists and built the institute’s profile in a medical culture that largely favoured clinical observations over laboratory research.

In one telling anecdote from the 1930s, Kellaway was showing a scientific colleague around the institute when he saw Macfarlane Burnet crossing the courtyard. Kellaway pointed at him and said to his colleague, “if I’m right, he will become one of the world’s most distinguished scientists.”

Opening up new funding sources

As to finances, in 1927 it was his approach to the federal government with a proposal that it fund antivenom research which overcame skepticism in the bureaucracy about the value of funding research and set an enduring precedent. The system of Commonwealth funding for medical research programs paved the way for the establishment of the National Health & Medical Research Council in 1936.

As Macfarlane Burnet remarked on his mentor, Kellaway’s influence “set Australia on a new path to achievement in medicine.” His innate parsimony helped steer the institute through the Depression.

Kellaway becomes a community leader

He likewise steered the medical profession through the sensational Bundaberg disaster. On the weekend of 28 January 1928, 12 Bundaberg children died and five fought for their lives in hospital after a batch of the diphtheria vaccine was heavily contaminated with ‘golden staph’ (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria.

As a chair of the Royal Commission into the tragedy, Kellaway won widespread acclaim for raising the profile of medical research and reassuring the public at a time when mass immunisation programs were only just gaining acceptance.

To war, again

The advent of World War II ended Kellaway’s personal research career even as the institute continued to thrive. As an army colonel, he occupied key positions on medical services in the armed forces, helping establish a reliable blood transfusion service and shifted researchers’ focus to the tropical diseases afflicting Australian soldiers in the Pacific theatre.

Kellaway’s legacy

When what is now the Royal Melbourne Hospital moved from Lonsdale Street to its new premises in Parkville, he shifted the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute to custom-built laboratories in a wing abutting Royal Parade. He devoted enormous amounts of his time to overseeing its design and administrative negotiations.

Having secured the institute’s future, in 1943 Kellaway’s administrative skills and political nous were recognised when he was recruited to head the research laboratories of London’s crisis-ridden Wellcome Foundation. Arriving in 1944, his contribution helped sustain what has become the world’s second-richest medical charity and foremost medical libraries.

Though he loved the great outdoors, bird photography and fly-fishing, Kellaway’s persistent vice, cigarettes, brought about his death from lung cancer in 1952. His passing brought tributes to the man’s warmth, good humour and “genius for friendship”.