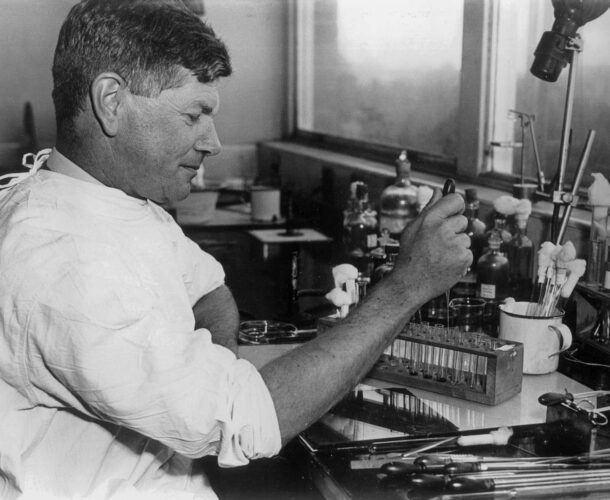

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet becomes the third director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (1944-1965).

A future Nobel laureate and one of Australia’s most revered scientists, Burnet makes significant contributions to bacteriology, virology and immunology over his 59-year career, most of which are spent at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

Under his leadership, the institute expands in size, scope and profile. Midway through his term as director, a change in research focus and breakthrough discoveries establish the institute as a world leader in immunology research.

Contemplating Burnet and his impact on the institute

In the top floor eyrie of the modern Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, surveying the bustling tea room culture that has nurtured so many of its stories, is a portrait by Clifton Pugh of legendary director and Nobel Prize winner Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet. It inspires contemplation of the man who had such a defining and enduring influence on the character and achievements of the institute.

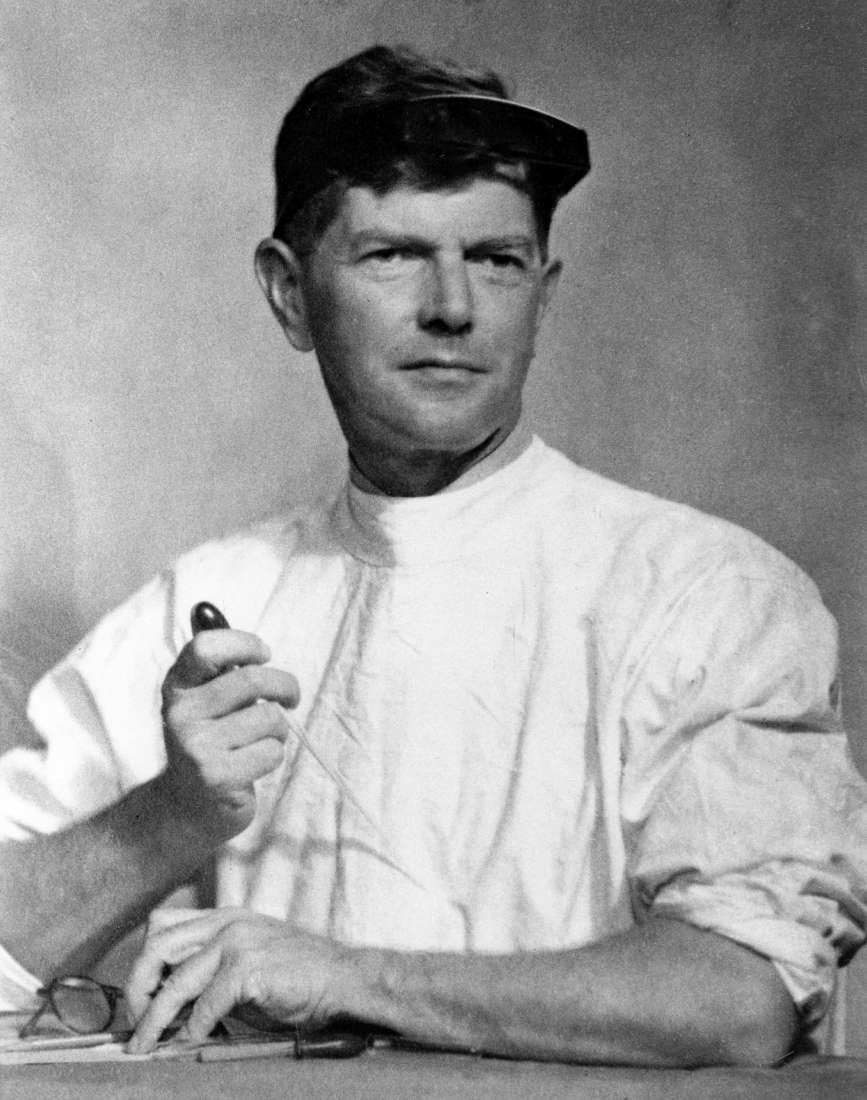

Burnet looks formidable, stern, remote, proud – if a little defensive. Sir Andrew Grimwade, the long-time institute board member and president who gifted the painting, recalls that some protested when it was unveiled “’oh, that’s far too tough’, but the researchers who worked here said ‘yes, that’s him’”.

Burnet’s biographer, Christopher Sexton, says that Burnet liked the picture, preferring Pugh’s rendering of him to the gentler, “too pretty” portrait by Sir William Dargie that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra.

An insight into Burnet’s personality

Whether Burnet appreciated Pugh’s picture for its artistic merit or its honesty is hard to say. Burnet was an ardent student of pictures, and an artist himself. A passionate naturalist, throughout his life he took his watercolour paints and brushes on long rambles through the bush. For a time he took night classes in life drawing and his surviving daughter, Liz Dexter, recalls how she and her brother and sister pored over the nude etchings he brought home.

But Burnet was also introspective, studying his own nature and circumstances, and would have acknowledged traits captured in the picture – his self-containment, a certain discomfort, the aloofness of the chronically shy. Though he had a high regard for his intelligence and achievements, Dexter remembers he nonetheless envied the easy charm of outgoing types.

He did overcome this obstacle of reticence long enough to fall in love with a vivacious schoolteacher, Linda Druce (Dexter’s mother). His letters to her included the observation that “one of the pleasantest prospects before me is a wife who has the knack of making friends. You will have to manage that side of the business my dear”. (He also promised his bride a trip to Belgrave, where if the sight of lyrebirds dancing at dawn did not quicken her heart, “there’ll be a divorce!”.)

Ian Mackay describes Burnet

When Professor Ian Mackay, a long-time collaborator with Burnet and one of the corps of great scientists whose work built the institute its international regard, was drafting a history of their work on autoimmunity, he described Burnet as “severe”, but removed the word after conceding to Dexter’s objection that it was not a fair portrayal.

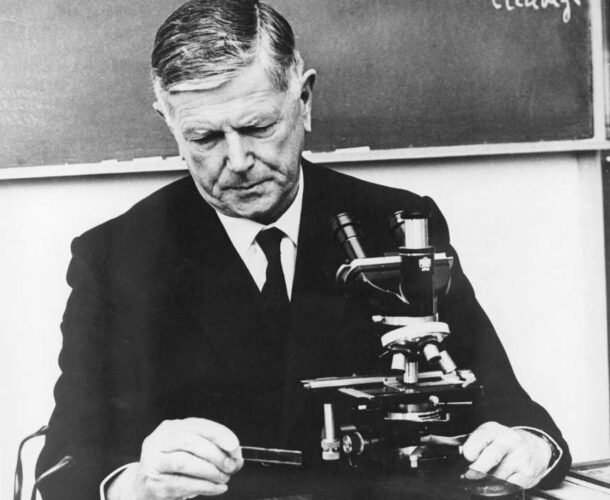

But Burnet was authoritative, he just did things his way,” Mackay says. “I recall the day when he assembled the staff of the institute, such as it was then … and said ‘we are switching from virology to immunology’.

He had almost God-like dimensions. This was handed down from above and that was the end of it.” Despite their many years of “very close” collaboration, “first name usage would have been unthinkable,” Mackay says. “I don’t think that throughout his life I ever ceased calling him ‘Sir Mac’.

Understanding Sir Mac

Biographer Christopher Sexton, who spent every Friday for six months interviewing Burnet in the early 1980s, found him warm, wise and open, though he occasionally glimpsed the steely “Sir Mac” of legend.

Sexton’s 1991 book, The Seeds Of Time1, cites criticisms by some that Burnet was dogmatic, opinionated, a name-dropper. It also draws a picture of a man who endured depression and isolation in his youth, but found connection and purpose in family and work. The man Sexton encountered, toward the end of his life, had “an elusive air of simplicity, honour and integrity”.

Dr Margaret Holmes, a scientist and stalwart presence at the institute for 50 years, says simply that “people used to say Sir Mac was hard to talk to, but I never had any trouble. We’d both grown up with and had a love of Kipling”.

Early years and influences

What was without question was Burnet’s rare brilliance.

“Mac” Burnet hailed from Traralgon and Terang, the second of seven children born to a Glaswegian bank manager and a Western District schoolteacher’s daughter. His elder sister was intellectually disabled, and the lifelong care she required and the shame her circumstances invited in that era profoundly shaped the dynamics of the family.

A smart and solitary child, Burnet immersed himself in books and in nature. He visited birds’ nests and collected beetles. Charles Darwin became his hero. He won a scholarship to board at Geelong College, an unhappy experience, but emerged to excel in medicine at the University of Melbourne.

In 1923 Burnet, now a medical graduate, arrived at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute to take up a position as pathology registrar. With encouragement from director Dr Charles Kellaway he pursued research qualifications in the United Kingdom, undertaking training in microbiology from 1925 to 1928. He then returned to the institute, where he remained until his retirement in 1965.

The third director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

Burnet took over from Kellaway as director in 1944. He focused much of the institute’s effort on developing an influenza vaccine. While this quest eluded him, Sir Gustav Nossal, who succeeded Burnet as director in 1965, observed that it inspired some paradigm-shifting science from the likes of Gordon Ada, Alfred Gottschalk, Eric French, Frank Fenner and Alick Isaacs.

In 1957 Burnet shifted the focus of the institute to immunology. Nossal suspects that in part this was because molecular biology and biochemistry were becoming dominating threads in virus research, and Burnet wasn’t interested in those.

“He didn’t like complex equipment,” Nossal says. “In a way the field was moving away from him, whereas immunology at that stage wasn’t well developed and he could use his incredible talents in a sort of Darwinian-style thinking about the immune system and make a big contribution.”

Today Burnet’s lack of regard for molecular biology, which so powerfully shapes evolving research, seems unfathomable. Critics point to it as the conceit of someone who can’t conceive of the game continuing without them. Sexton explains it as the argument of the general biologist “concerned with whole organisms and their interaction with each other and with their environment”.

Burnet maintained that because the human organism was so complex, no amount of insight into how individual cells functioned, or the genes controlling them, could lead to practicable means of influencing sickness and death.

Balancing public and private lives

Burnet became Australia’s most decorated scientist. Sexton observes that he never fitted comfortably with the Melbourne Establishment, but did become rather partial to royal gatherings. As well as the Nobel Prize he acquired three knighthoods, the Copley and Royal Medals of the Royal Society, and the highly rare honour and personal gift of the Queen of his appointment as the Senior Member of the Order of Merit.

In his personal life Dexter recalls him as a father who had breakfast and dinner with his family most days. Who took his wife breakfast in bed on Sunday mornings and his children to his laboratory to give her the morning off. Who sat by the fire in the evenings creating painstaking indexes from the latest journals.

He walked with his dog every day and with other naturalists, in the Wallaby Club, most weekends for 50 years. He was shattered when a colleague, Dora Lush, died after pricking her finger in the laboratory and was infected with scrub typhus. He turned down a plum position at Harvard Medical School because he wanted his children to grow up in Australia.

I think he also wanted to show that he could succeed in Australia, and that he could build the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute up to emulate these great institutions that had welcomed him in America and England,

Dexter says.

Setting up a bright future for the institute

Having achieved that ambition, he sought to lock in the institute’s future by handpicking the right successor for the next era.

“He gave an awful lot of thought to that,” Dexter recalls. “It was for the institute, it was his baby, and he wanted it to continue with strength. Gus (Nossal) was his complete opposite – a marvellous communicator, and yet a wonderful scientist. He looked for someone who made up for the things he knew he was weak in.”

He chose well. Sir Gustav Nossal led the institute for 31 years, increasing the scope of research and transforming it into the dynamic organisation it is today.