In March 2012, Dr C Glenn Begley was lead author of a Nature paper that ignited a sensation. It wasn’t about a triumph of medical research – rather it catalogued the failure of many scientists, including those in leading institutions, to do rigorous research.

The paper documented efforts by the US pharmaceutical company whose laboratories Begley then oversaw, Amgen, to reproduce the cancer research findings of 53 ‘landmark’ papers. In 47 instances, the results could not be replicated. The tally exposed how errors and sloppy science were undermining the race for more effective cancer drugs.

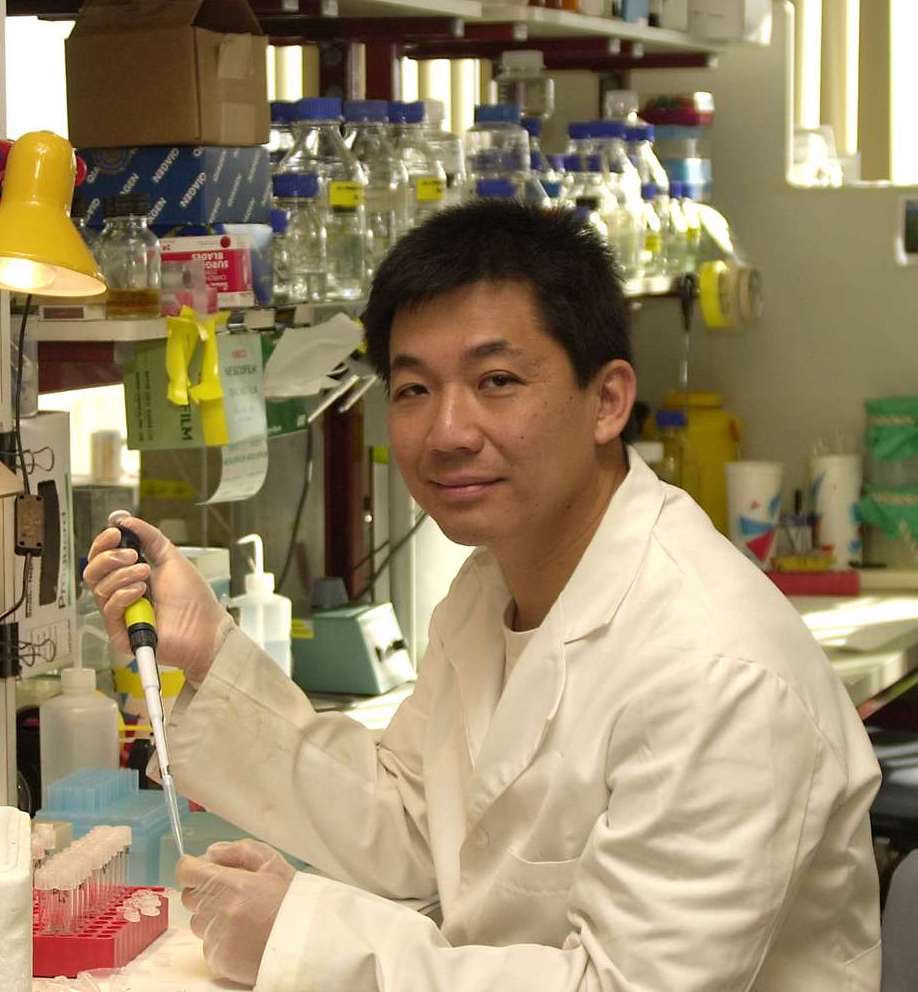

Apprenticeship with Metcalf

It was an insight that Melbourne-born-and-raised Begley found particularly shocking given his own research apprenticeship in the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute under the scrupulous, exhaustive tutelage of Professor Don Metcalf through the 1980s and 1990s. “Certainly while I was at the institute there was never any question that the data had to be solid.

“What Don taught me was that the most important issue was scientific rigour,” says Begley. “There was never any doubt that what we published would be right. If it meant that we were second, then so be it. We would rather be right than first.

“The group as a whole worked together to make sure that no scientific stone was left unturned. We were responsible for each other’s data – the critique of the science was really intense.”

Begley came to the institute to begin a PhD under Metcalf at age 27, having already completed training as a physician at the University of Melbourne and the Royal Melbourne Hospital. His venture into the laboratory was strategic, a step toward his ambition to become a professor of medicine, if a bit reluctant. “I used to denigrate research, saying it really should be done by people with a PhD, that it was a waste of an MD.”

Seduced by science

What he came to see, in observing Metcalf and director Professor Gus Nossal, was that while they might not be seeing patients, they were indeed practicing medicine – “their work was so focused on making a difference”.

Having ventured into research, there was no going back. “I was seduced by science. I got infected, and have never been able to leave since.

“It was just the excitement and frustration of discovery. Day after day, nothing happening, and then – something. You know something no-one else in the world knows, for that brief moment. It is a very heady experience.”

Begley did keep a foot in both camps, having been encouraged to pursue the still fairly novel track of the physician-scientist, continuing work as an oncologist at The Royal Melbourne Hospital as well as pursuing his PhD research.

Watching the benefits of CSFs

He was a part of the Metcalf laboratory team that identified the human G-CSF (colony stimulating factor) molecule now used internationally and routinely to fortify cancer patients to endure the rigours of chemotherapy treatment.

“We were treating animals for the first time in the world with these recombinant molecules. I was coming into the old Hall Institute at 2am to do the injections.

“But then to analyse those animals and see what was actually happening in them, and to imagine what that might mean for patients, it was really very exciting.”

After leaving the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for three years to continue his training and research at the US National Cancer Institute, Begley returned to the institute for another chapter in the G-CSF story, showing that they could move stem cells from the bone marrow into the blood, where they could be harvested and used for transplantation.

It revolutionised treatment. “We were the first in the world to show that was effective, and it has had an enormous impact,” Begley recalls.

“Something like 20 million people have been treated with CSFs, hundreds of thousands have benefited from this different approach to bone marrow transplantation. It was frankly wonderful to have a part in that.”

Curing hepatitis B

Today Begley, in his role as chief scientific officer of US biotech company TetraLogic Pharmaceuticals based in Malvern, PA, is again involved with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in a research partnership exploring the potential of a cancer drug the company developed. They are conducting phase 1/2 clinical trials of the drug, birinipant, for treating myelodysplastic syndromes, a pre-leukaemic disorder, and ovarian cancer, and a trial to examine its use to cure hepatitis B.

Birinapant picks up on the landmark work of Professor David Vaux and Professor Andreas Strasser at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute on cell death, using molecules to intervene to ‘inhibit the inhibitors’ of cell death. The failure of cells to die can cause or exacerbate many diseases, including cancers. That work was followed up by Dr Marc Pellegrini’s group at the institute, who made seminal observations about the role of cell death in infectious diseases.

While there is still a long way to go, and Begley cautions that life in the biotech industry is “mostly about managing failure, because almost everything we do will fail”, the signs are positive enough for him to hope to again find himself instrumental in a transformative moment.

Bright future

The partnership is testament to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute’s endurance at the front line of research, Begley says. “Its reputation is very strong, built on quality science, not flashy science – on robust, rigorous data.

“The future is very bright so long as that remains the focus, and I think that is so deeply ingrained that it will continue.

“I think too that there is also, perversely, some advantage in being remote. Australian science isn’t quite as influenced by what is going on around the world. People aren’t immediately following the latest sexy trend.

“PhD training at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute is still outstanding – as good as anywhere else in the world and better than most. I’ve told my kids if they want to do a PhD, that’s where they need to go.”