Over five decades she makes significant contributions to immunology research, is central to the successful management of the institute and becomes a world-class expert in laboratory mouse care.

Of mice and men

Over more than 50 years of dealing with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute’s mice and – predominantly, in the early years – men, Dr Margaret Holmes learned how to manage the former with kid gloves and the latter with an iron fist.

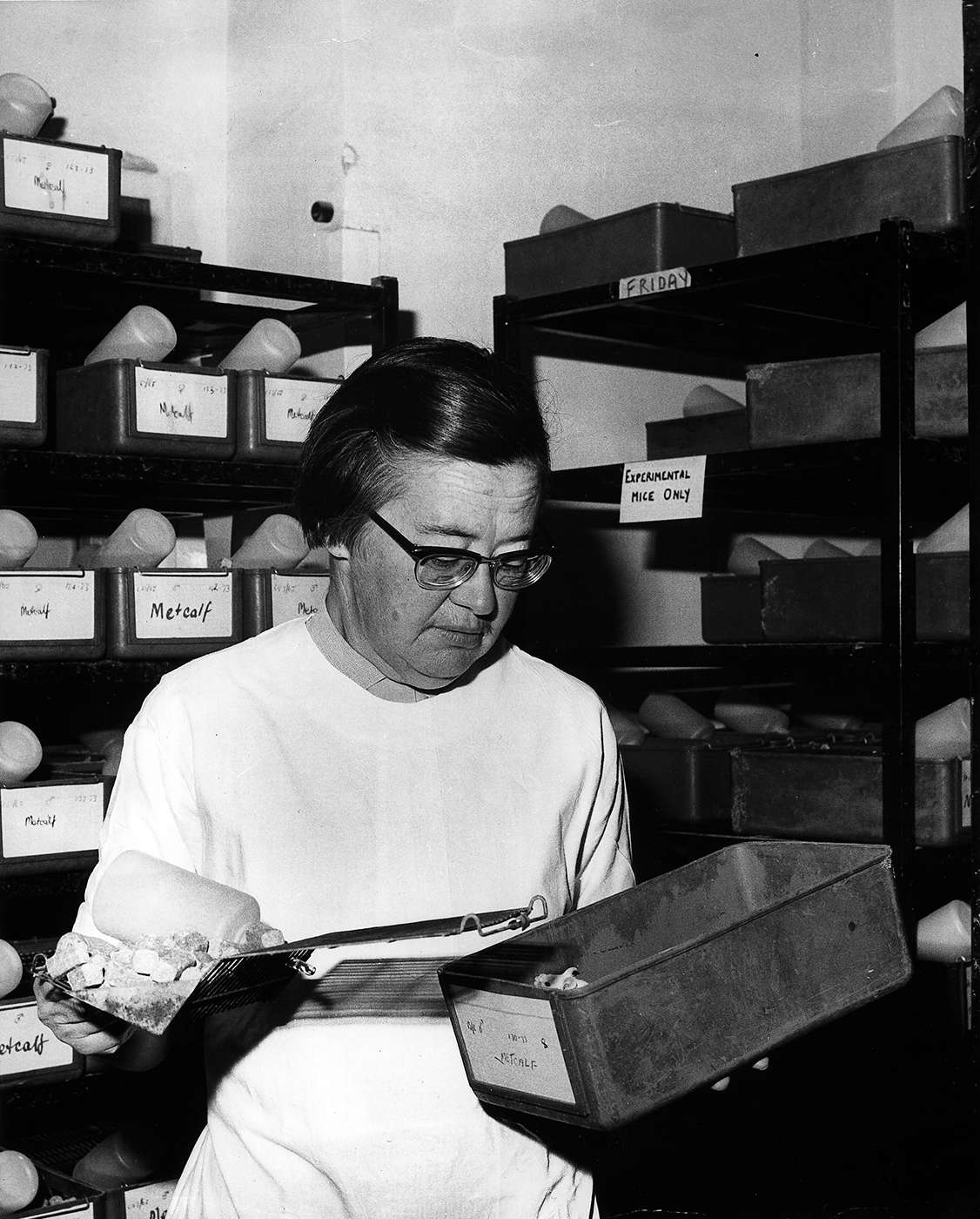

Her skills in breeding and nurturing laboratory mice set the benchmark in Australia, and gained international recognition. The longevity, painstaking pedigrees and health of these creatures provided the bedrock on which the work of Professor Jacques Miller, Professor Don Metcalf and many more of the institute’s watershed discoveries and reputation were founded.

She describes her role as three pronged:

- Managing the technical staff

- Managing building projects

- Managing the animals

Her wrangling of the scientists – and her own role straddled the laboratory and administration – was no-nonsense, pragmatic and discreet. She once stepped in to stop an irate scientist taking his frustrations out on a junior, but still won’t name names.

The institute family

She had occasion to chauffer two directors to work over the years:

“Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet was usually driven around by the manager Arthur Hughes (Hughsy) but when Hughsy wasn’t available I did. Sir Mac didn’t like to drive because he liked to keep his mind on other things rather than the road and the vehicle. People used to say Sir Mac was hard to talk to, but I never had any trouble. We’d both grown up with and had a love of Kipling.”

When she gave Sir Gustav Nossal a lift from their Kew neighbourhood, “we used to discuss how the staff should be organised at the institute. I used to put my 10 pennyworth in on that one.”

Holmes was trained in an era when money was so tight that the institute recycled lengths of string. Her thriftiness provided the wherewithal to push the scientific boundaries, even if it appeared to thwart the ambitions of some. “If someone asked for something, you’d always say no the first time,” she says. “If they really wanted it, they would come back again.”

“Gruff in manner, Margaret inspired fear in any technician caught doing the wrong thing, but any institute person in trouble soon came to value her heart of gold,” Nossal observed in his history Diversity and Discovery. “The Hall Institute has never had a more loyal or single-minded servant.” Holmes happily declares “I had an institute instead of a family”.

Early life and career

Holmes’ involvement with the institute began in 1938, the week after she finished at Ruyton Girls School. Her heart’s desire was to study medicine, but with five children, the family didn’t have the means to support her. So she set out to support herself.

Curiously, mice were her entrée to the institute, long before they became a laboratory staple and her specialty. Her entrepreneurial father had made some contacts at the Hall Institute when he dabbled – not successfully – in breeding and selling laboratory mice. He came to know Fannie Williams, scientist and World War I veteran, and it was through this connection that young Margaret found her job and encouragement to buck the constraints on women. “I admired her extremely”.

“At that time women still couldn’t get a permanent job as a technician at the institute due to concerns that they would get married and leave. The institute couldn’t risk having pregnant women working there because of rubella. So we had to get past that one, that not everyone was going to get married, and that we had to be properly trained – we had to fight for that.”

The institute Holmes joined had just a total of 12 staff. Her duties included buying their cakes for morning tea, washing their dishes, and collecting the laundry. She also recalls collecting blood samples from soldiers heading off to World War II and stamping the types in their pay books – among them that of General Thomas Blamey. She says “this is how I got into the scientific staff really.”

Embarking on a life of science

By 1940 Holmes had determined that she wanted to be a scientist, and enrolled part time to study chemistry at night at RMIT – the only female in the class – later also taking up studies at the University of Melbourne.

When the director, Dr Charles Kellaway, discovered that she was paying university fees, he gave her a pay rise from 25 to 35 shillings a week to cover the cost.

She says: “I was very grateful for that. He used to stamp up and down in the corridor and shout “Eureka Eureka” when things went well, broadcasting through the institute. He looked after me. He was a good man.”

In 1942 Holmes quit work to study full time, and obtained a PhD investigating Haemolytic streptococci, the bacteria that causes tonsillitis and rheumatic fever. She won a scholarship to study in London, where she spent several years employed by the Medical Research Council working and travelling across Europe when opportunity allowed.

Kellaway, who was by then in London as scientific director of the Wellcome Foundation, continued his support of her. “He took me to a dinner in Oxford. Often I would end up the only female in these situations, and they didn’t know whether to offer you a drink or what to do with you. You could get in some funny situations.”

Returning to the institute

When she came back to Melbourne in 1953, Holmes got a job in the laboratory at Fairfield Hospital. “It was very boring, with nobody to talk to scientifically,” she recalls. “The young medicos there only talked about their cars and their girlfriends.

“So I was very glad when Bill Keogh said ‘you shouldn’t be there – I will talk to Burnet’,” who was then director. (Dr Keogh was a mentor and critical facilitator to the careers of many scientists – among them Professor Don Metcalf.)

Holmes was offered a position partly in the laboratory work and partly overseeing the small corps of female scientific staff.” By then she had decided she was less interested in laboratory work herself than in providing the best environment for the researchers.

A pioneer in scientific mouse breeding

It was in this realm over the next decades that she provided the infrastructure and staffing integral to the institute’s successes through a golden era of discovery. As Nossal has said in his tribute, “Dr Holmes made herself a great expert in everything pertaining to mouse breeding and husbandry, including the maintenance of germ-free and specific pathogen-free status.”

She was a pioneer in the field, figuring it out as she went. “Jacques [Miller] wanted germ free animals that had no bacteria anywhere, and had to live in isolators.” For a period these very expensive creatures were housed at the university – “and I was standing outside one evening and saw the lights go out”. Without power the isolators would fail and the mice would suffocate, “so I went racing across Elizabeth Street in the peak-hour traffic to get up the stairs to save them”. She did, and by morning had arranged for the installation of back-up batteries.

In the 1970s she provided critical input to the design of the institute’s animal breeding facilities at Kew – the famous “mouse Hilton” – and through the 1980s liaised between scientists and architects to shape the new Parkville buildings.

With compulsory retirement at 65, she reluctantly retired in 1986 and took her expertise to China, and helped scientists there establish a mouse breeding capability and the Institute trained Chinese staff to look after the mice.

Celebrating success, together

A cherished memory is of the day news arrived that Burnet had won the Nobel Prize.

“We thought ‘we’ve got to fly a flag’, so we went to the hospital and asked if they had a flag, and the only thing they could provide was a Union Jack. And I said ‘we want an Australian flag’. So we went and bought one.

“There was a flag pole on the top of the building, but someone had pinched the guy ropes. But we got the flag flying, and people from the university were ringing asking ‘why has the institute got a flag up?’ And word got around.”

They celebrated at a restaurant in Lygon Street. “We persuaded them we needed a special meal, and we had it in the back garden, and could drink to Mac’s health.”