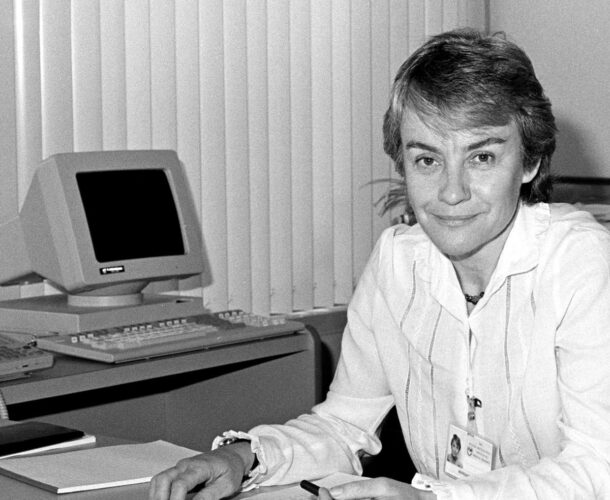

Dr Margaret Brumby AM successfully applies for the position of Walter and Eliza Hall Institute general manager. She goes on to hold the position for almost two decades.

Christmas jobs and cancer labs

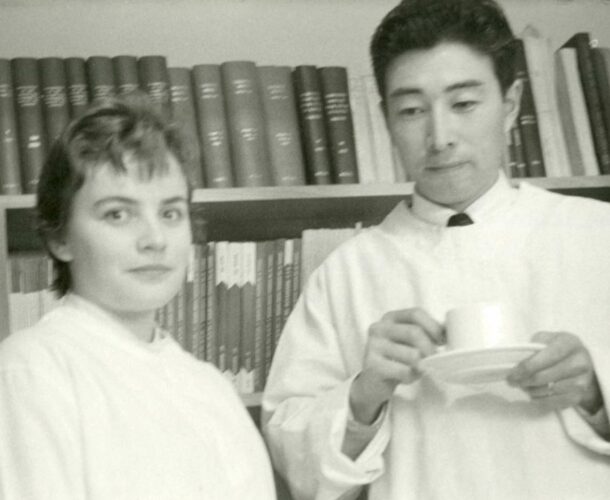

Brumby started her undergraduate degree in science at the University of Melbourne in the late 1950s when she heard that students could obtain a ‘Christmas job’ in the laboratories of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Brumby liked that after a morning’s work, a laboratory technician could be persuaded to show her around the research lab. Returning the following summer she asked to visit the cancer research lab.

Normal before the abnormal

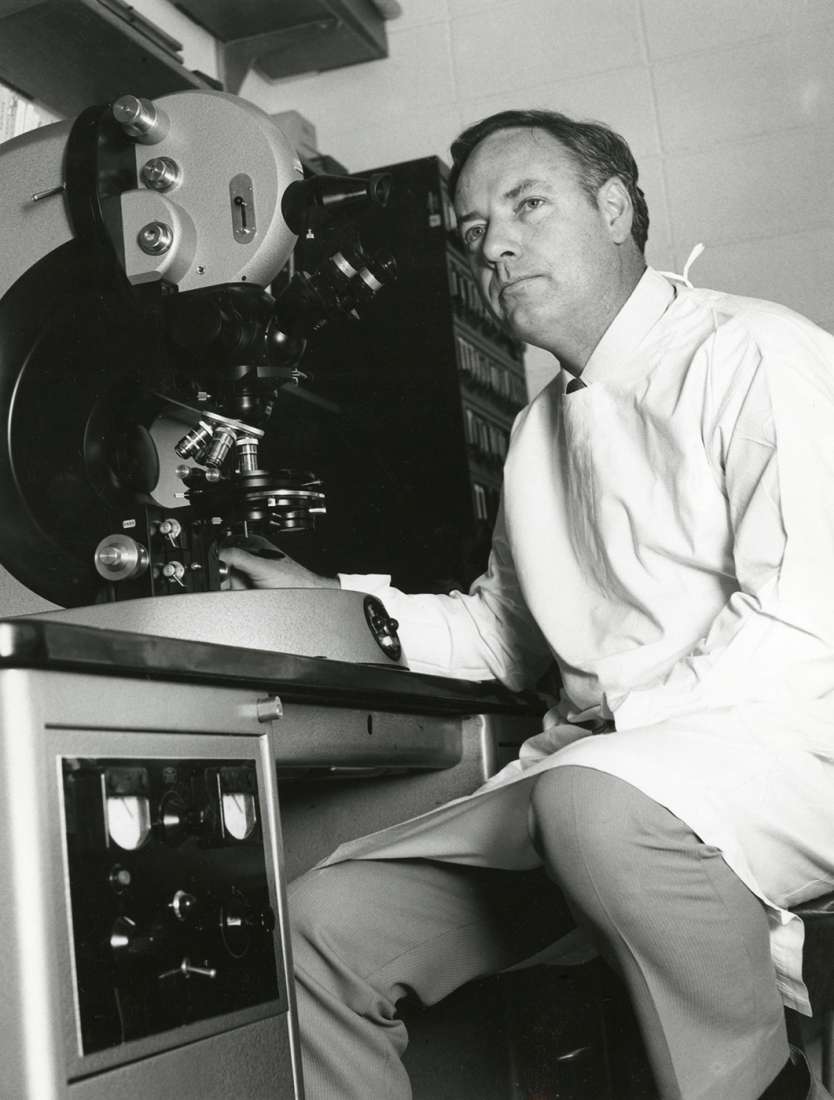

Eventually Brumby plucked up the courage to approach the ‘Mr Big of cancer’ Professor Donald Metcalf. “I asked him what subjects to do in third year,” she recalls. “I expected him to say chemistry or pathology. But he said, ‘you have to understand the normal processes before you can understand the abnormal.’ He told me to study subjects like physiology and bacteriology.”

Brumby heeded his advice, finished her undergraduate degree and returned to the institute to complete her Master of Science in Metcalf’s lab. But her scientific career was short-lived, due mainly to the lack of child-care and her husband’s appointment to London. Brumby took up teaching biology at both secondary and tertiary levels, but never forgot the atmosphere and excitement of the institute.

A return as manager

In late 1986 Brumby saw an advertisement for the position of Walter and Eliza Hall Institute general manager and successfully applied.

The institute had recently moved into its first purpose-built building and staff numbers had grown to 350. But Brumby recalls the institute was still “one big family, with a minimal organisational structure, no formal reporting or contracts of employment. The science was still relatively simple; the head of a lab could direct a whole project.”

From dukes to dogs

Brumby’s early tasks encompassed organising official visits to the new building, including for the Duke of Edinburgh and Indonesian minister BJ Habibie. Margaret Thatcher’s visit was particularly memorable as it involved extensive negotiations with government security personnel requesting, among other things, that sniffer dogs roam the institute’s sterile laboratories — ‘unacceptable’ was Brumby’s response.

Thatcher’s visit had no advance publicity, so the appearance at reception of a dirty envelope addressed to the prime minister saw Brumby cowering in the doorway as the grim-faced security officers prized it open with a knife. “Dear Mrs Thatcher,” the letter read, “my mum turns 90 next week and she’d love a letter from you.”

Other managerial duties ranged from collating material for the five-yearly reviews — each more complex than the last — to convincing the authorities that the institute’s PC3 containment lab could securely accommodate imports of malaria mosquito larvae. “We had sought advice from our Scottish colleagues about how best to frame our application. They replied that their own authorities had been unfazed because any escapee mosquitos would immediately freeze to death in their chilly climate!”

Witness to history in the making

Brumby still remembers the exhilarating day in the cancer lab when a young postdoctoral scientist was examining the blood of a cancer patient injected with G-CSF: a hormone that controls white cell production in the bone marrow. “He noticed to his surprise that many red blood cells still had the nucleus in them, which meant they were newly released cells from the bone marrow. It was reasoned that treating chemotherapy patients with CSFs may enable these patients to fight off infections during their treatment. CSFs have now been used to treat millions of patients world-wide.”