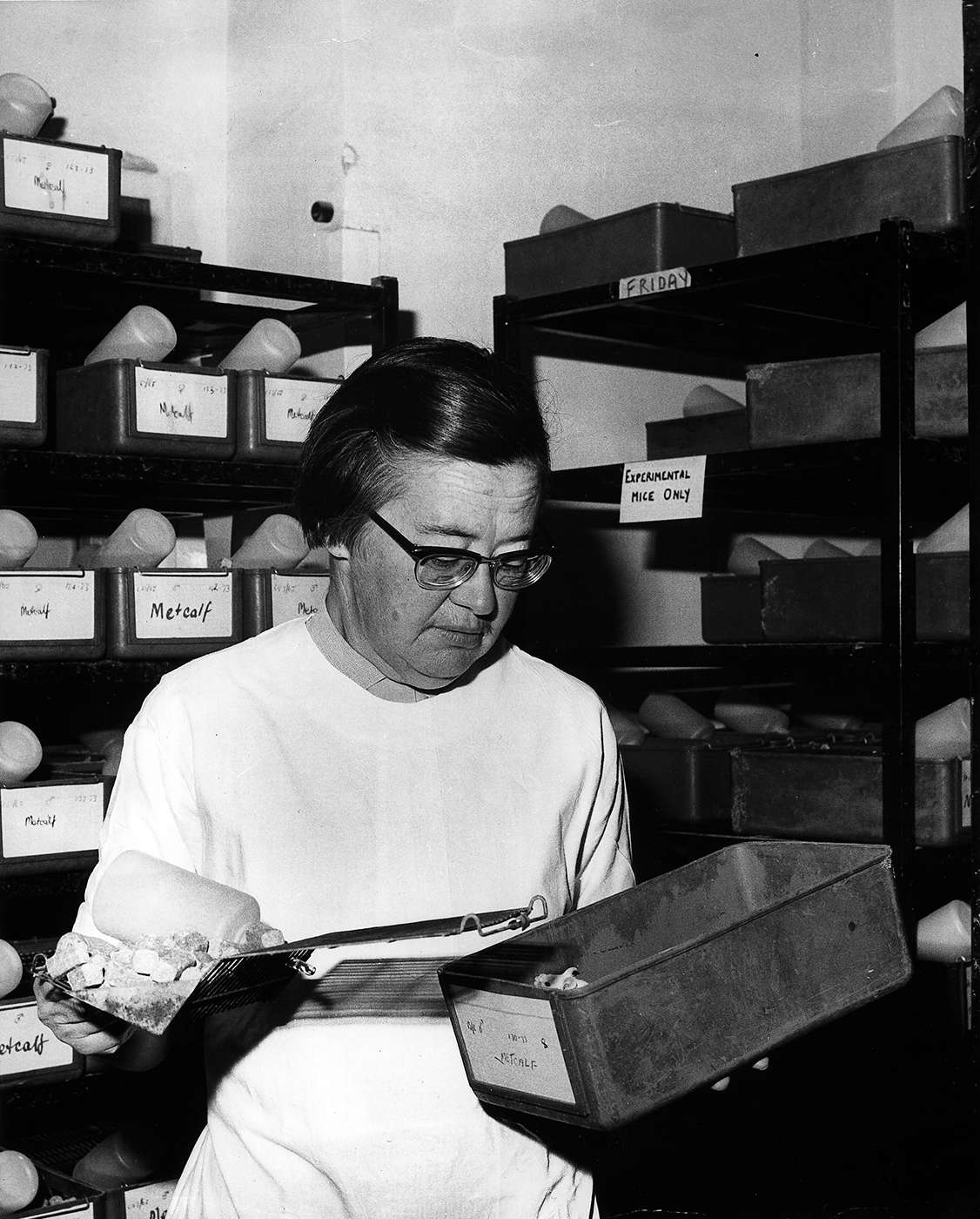

In the early days of the Clinical Research Unit, one of the central interests was chronic active hepatitis.

Clinician-scientists at the institute were perplexed by some cases of hepatitis that did not seem to be caused by an infection, and could not be explained by other causes.

It predominantly affected women, causing jaundice, bleeding, and eventually coma, and was often fatal in less than two years.

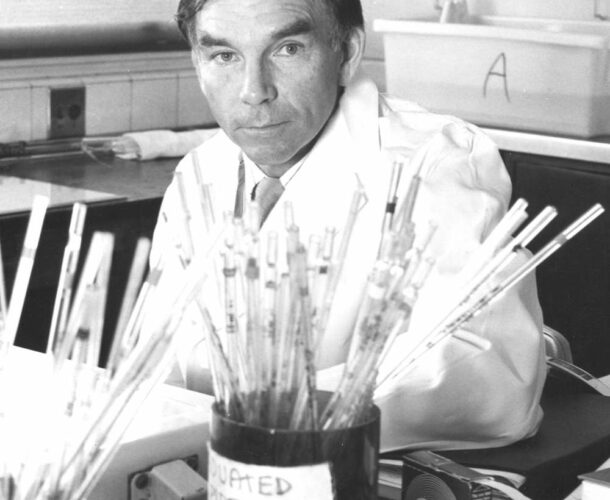

While studying viral hepatitis, Dr Ian Mackay and Carleton Gadjusek ‘serendipitously’ develop the autoimmune complement fixation test.

New autoimmune test discovered

“In those days” Mackay says “it didn’t seem it was a chronic disease, and yet we gathered in the Clinical Research Unit a group of young women who had a severe, progressive, frequently mortal type of illness.”

Mackay wondered if their hepatitis might be an autoimmune condition, “nothing to do with the virus”, and seized the initiative to find out.

An American researcher, Dr Carleton Gajdusek – who would later win a Nobel Prize for his work on kuru – was visiting the institute and trying to develop a specific test for viral hepatitis.

Unbeknown to Gajdusek, Mackay slipped a batch of sera from his patients into the next round of tests. The test didn’t work on viral hepatitis cases, but produced some striking positives using Mackay’s samples. This yielded a revelatory diagnostic test – the autoimmune complement-fixation test – that clearly indicating certain patients were mounting an antibody attack on their own tissues.

Mackay’s role in this was little known. In his history of the first 50 years of the institute, Macfarlane Burnet referred to Gajdusek’s discovery of the diagnostic test as having been facilitated by “a form of serendipity which need not be elaborated”.

“They didn’t include me on that paper, which is something I feel mildly pained about because that was the discovery element,” Mackay recalls today. But it did bring insight, opening the door to effective treatments that quickly turned what formerly had been a death sentence for young women into a manageable condition.

Chronic hepatitis is an autoimmune disease

As Mackay and Warwick Anderson described in their book Intolerant Bodies:

“It looked as though this group of patients was overproducing antibody against normal liver tissue, not against a virus. Gadjusek and Mackay had, in effect, identified chronic active hepatitis as an autoimmune disease.”

This clearly showed that some patients were mounting an immune response to their own tissues, and indicated that the blood from these patients had auto-antibodies that were attacking their liver, causing autoimmune hepatitis.

Mackay and Gadjusek had developed an effective test for diagnosing autoimmune disease.

The test also gave positive reactions in people with what are now known to be autoimmune diseases, such as lupus (systemic lupus erythematosus), macroglobulinaemia and Hashimoto’s disease (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis).