Institute researcher Dr Alfred Gottschalk discovers influenza viruses contain an enzyme, neuraminidase, which releases the sugar sialic acid. Sialic acid is an important sugar molecule in humans, controlling interactions between different cell types in the body.

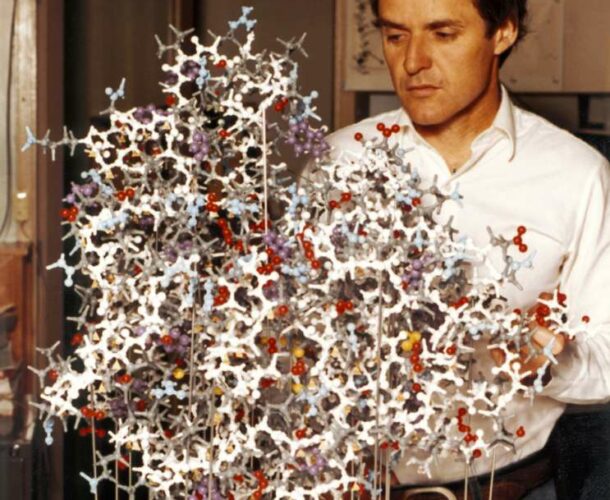

Gottschalk’s discovery was essential to understanding how influenza viruses infect cells. It paves the way for development of anti-flu drugs such as zanamavir (Relenza®) by Professor Peter Colman and his colleagues while at the CSIRO.

Gottschalk’s arrival

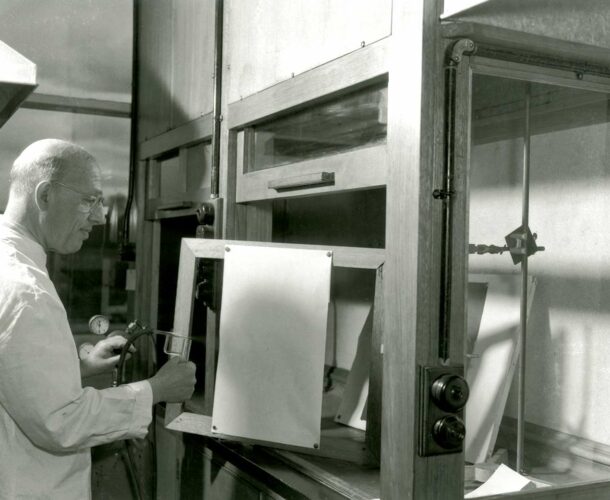

Dr Alfred Gottschalk was only 45 but had already lived several lifetimes when he sailed to Melbourne from Germany, via England, in July 1939.

As a young man he had served in the German military’s medical corps in World War I, yet due to his Jewish heritage – and despite his Catholic faith – he became a refugee from his country as World War II loomed. By then he had qualifications as both as a medical practitioner and a biochemist, with appointments at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin and later as director of biochemistry at Szczecin hospital in Pomerania, a role he was forced to relinquish because of the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany.

Arriving in Melbourne with his wife and small son he was offered a modest stipend by Sir Charles Kellaway to start work at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Initially he worked on yeast enzymes and fermentation. But from 1947 he joined the virus department and embarked on work under Dr Frank Macfarlane Burnet that would yield watershed results.

Infections and influenza

In that era the institute’s key area was infectious disease. Burnet had a deep interest in influenza having witnessed in London, in 1933, the first experiments where the virus was cultured into a ferret, and then into a man.

Today’s head of structural biology, Professor Peter Colman, takes up the story:

“Burnet noticed, in the 1940s, a very interesting thing. If you put influenza viruses in a test tube with red blood cells and mix them up, the virus will cause the red cells to agglutinate, which means that instead of settling (like sediment) to the bottom of the test tube the red cells sort of form a three dimensional network, they are suspended in the solution somehow by the virus. But if you let the whole thing sit there a while the agglutination reaction stops and the cells sink to the bottom.”

Burnet didn’t investigate further at the time, but an American scientist, George Hirst, did. “He figured out that when the virus and the red cells met each other, the virus changed the red cells, and it destroyed something on the red cell that let the virus stick to it.”

A watershed discovery

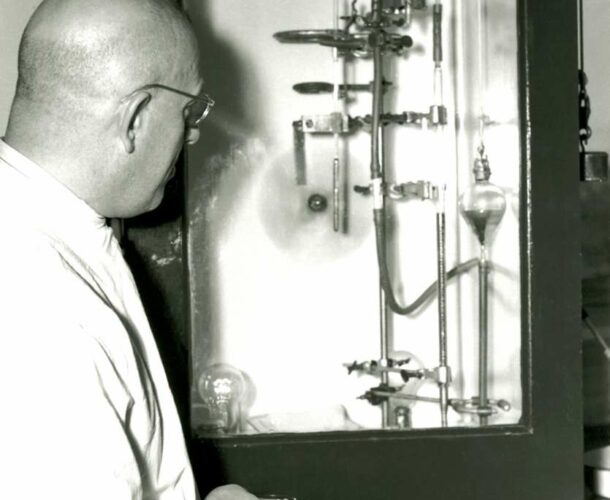

It was Gottschalk who worked out what it was that the influenza virus was cutting off the surface of the red cell. It is a sugar molecule called N-acetyl neuraminic acid, or sialic acid.

The influenza virus exploits this as an anchor to hitch itself to the red blood cell. This same receptor molecule is essential when the virus attaches to and infects cells in the upper respiratory tract. When the progeny viruses are escaping from the infected cell they must cut off this anchoring molecule to make their getaway. The viral protein that dues the cutting is called neuraminidase.

This insight had profound implications over many years, and underwrote Colman’s work leading CSIRO’s development of the first influenza drug (Relenza) in the 1980s.

In his history of the first 50 years of the institute (1915-1965), Burnet observed: “In the world of biochemistry the most important contribution of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute is regarded as Gottschalk’s discovery of the structure of the sialic acids and his recognition than an enzyme which I had characterised biologically was chemically a neuraminidase. Gottschalk’s work was masterly and it was definitive.”

Gottschalk applied himself to investigating this area until resolving it in 1958. “In all respects this work of Gottschalk’s is a classic example of how a simple biological phenomenon … can with a little good luck and years of hard work lead to a generalisation of the widest significance.”

A masterly career

In 1959 Gottschalk moved to the John Curtin School of Medical Research in Canberra at the invitation of Professor Frank Fenner, his friend and former colleague at the Walter and Elliza Hall Institute. He continued his research there until 1963, when he returned to Germany, and was welcomed into the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry.

Gottschalk died in 1973. His output of published work over his lifetime was immense – 216 research papers and reviews, and four books.

Fenner recalled him as a man whose scientific work was “characterised by his dedication, and by his meticulous attention to detail”. Outside the laboratory “he was a man of broad interests and interesting conversation, with a subtle sense of humor and a great fund of anecdotes”.