Widespread disease outbreak

In 1951, a mysterious disease outbreak in Victoria claimed 17 lives – nine of them children. In all there were 45 reported severe cases. Mostly the victims came from the north-west parts of the state, from communities sustained by irrigation channels feeding from Murray River.

The outbreak caused widespread public alarm and medical and scientific consternation. The symptoms included fever, headache, lethargy, vomiting, convulsions and cerebral dysfunction. In the worst cases the patients quickly slid into a fatal coma, and even survivors could be left with terrible neurological damage.

The sudden appearance of this deadly disease at the same time as the first rapid spread of rabbit myxomatosis along the Murray Valley fuelled public anxiety. Might there be some connection?

The scientist who put that concern to rest, along the way resolving questions around another decades old fatal outbreak, was Walter and Eliza Hall Institute virologist Dr Eric French. He set to work investigating the mysterious disease in collaboration with his colleague SG Anderson.

The case of two viruses

Their first notable achievement, observed their overseer and director, Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, was in recognising the similarity between the 1951 cases and those reported in another baffling outbreak back in 1917 and 1918.

The earlier outbreak had been investigated by Sir John Cleland, a Sydney microbiologist who had proved that it was not some form of poliomyelitis, as many suspected at the time. He’d achieved this by both studying its microscopic characteristics and by transferring the virus by injecting tissue from human casualties into monkeys and sheep. He recommended that it be called “X-Disease”.

Some 30 years later, French succeeded in isolating and characterising the 1951 virus, his findings quickly dousing any link to myxomatosis. He named it Murray Valley Encephalitis (MVE), for the area where it was found. “There is no shadow of doubt that what we studied in 1951 as Murray Valley Encephalitis was the same as the 1917-18 disease,” Burnet wrote.

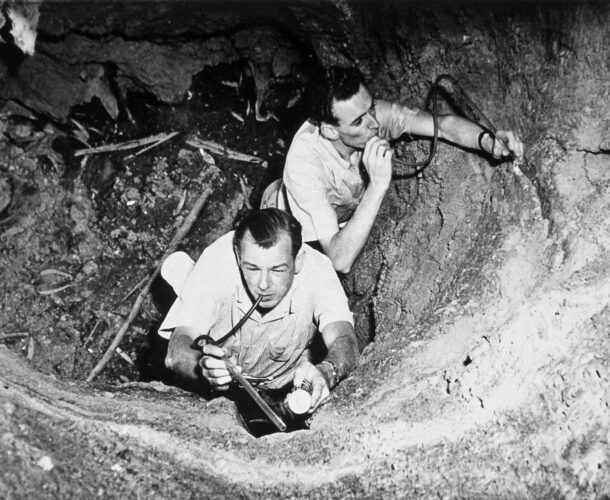

Virus transmission

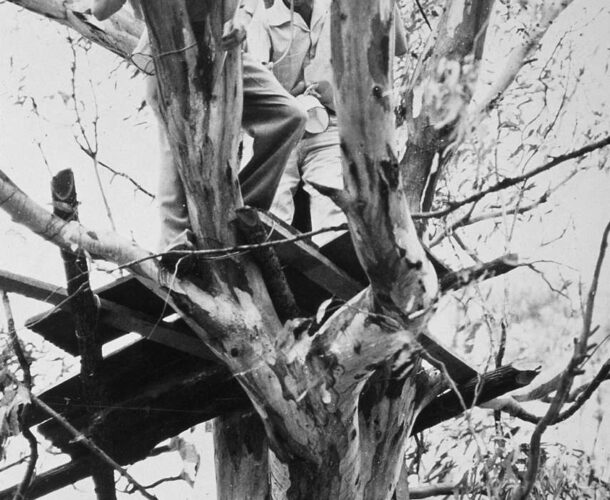

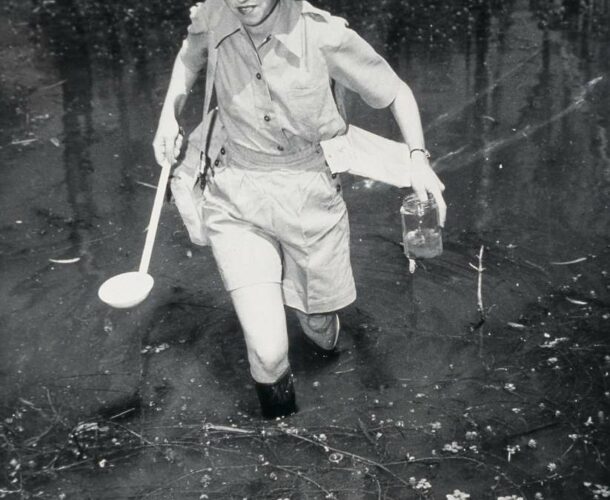

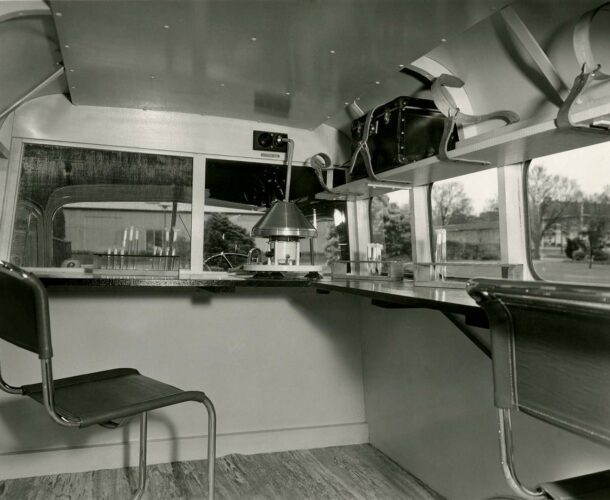

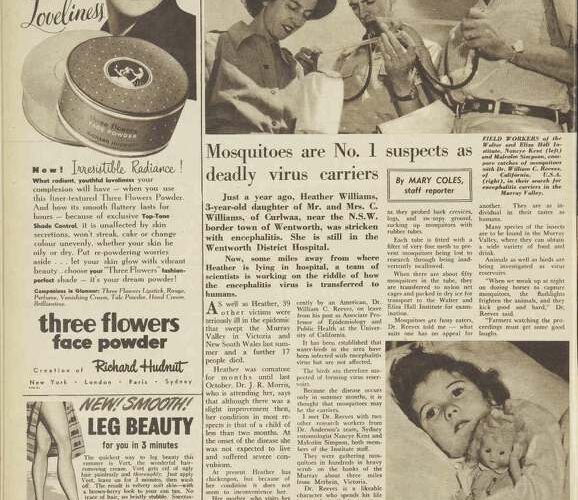

French’s institute colleagues later published papers hypothesizing that the virus was spread by mosquitos interacting with infected waterbirds, that it was endemic in tropical swamp areas of northern Australia and New Guinea and travelled south in heavy rainfall seasons – hence the long gaps between outbreaks. (There was another major outbreak in 1974.) The potential for further outbreaks is these days monitored using flocks of sentinel chickens kept for surveillance along the Murray.

The cohort investigating MVE in the 1950s were players in what is remembered as the golden age of virology at the institute. French also worked in influenza during the 1957 pandemic of Asian flu, and Burnet described him as “probably the first of several virologists around the world to show that this was the first appearance of a new type A2 and the forerunner of its spread around the world”.

Eric French, a pioneer in veterinary virology

French came to science the long way round. Born in Jamestown, north of Adelaide, on the rail line linking Perth and Sydney, he matriculated from high school by juggling night school with part-time work. After getting a job as a laboratory technician with the Adelaide-founded FH Faulding pharmaceutical company he moved on to the bacteriology department at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science in Adelaide, again juggling this with studies, obtaining a science degree in 1942 before going to war.

French joined the Australian Army Medical Corps and served in the Pacific and army hospitals in Australia until taking up a teaching position in bacteriology at the University of Adelaide and again returning to study. Burnet recruited him to the Hall Institute in 1947.

After his MVE virus breakthrough French was awarded fellowships to pursue his studies in the UK and the US. On returning to Melbourne he found the institute was beginning to re-orient itself from virology to immunology, according to a 2000 CSIRO history of the Animal Health Research Laboratory. “French sought other pastures and his move coincided with growing interest amongst the veterinary profession in viral diseases.” Burnet’s daughter, Liz Dexter, recalls that her father encouraged talented people such as French move on to widen their experience and scientific influence.

The recruitment by CSIRO of such a first-rate medical scientist to establish a veterinary virology program was regarded as an “enormous coup”.

French developed an intense interest in exotic livestock diseases and the measures required to keep them out of Australia. After his death in 2004, aged 89, he was remembered particularly for his “pioneering efforts in veterinary virology, (which) resulted in immense benefits to this country”.