The facility is the result of years of lobbying by the institute’s malaria researchers, including persuading governments that the institute can safely contain the exotic mosquito strains needed to advance their research efforts.

It is hoped that studying the very early stages of the malaria lifecycle will lead to new antimalarial drugs or a much-needed malaria vaccine.

Dr Sara Erickson is appointed to manage the new facility.

Breeding mosquitoes

Within the insectary researchers breed malaria-transmitting mosquitoes, allowing insights into how the parasite develops before being transmitted to humans, and then how it transforms itself within the liver before emerging to infect red blood cells.

A key objective of the insectary is to gain access to a mosquito previously not on the import list, Anopheles stephensi, which is naturally found in India and the Saudi Arabian peninsula, and is a very good vector of malaria parasites in the wild.

“What’s unique is that this species has been cultured in the laboratory, living in a little box, for over 30 years. So it is the easiest Anopheles mosquito to handle in the laboratory,” Erickson says. “There’s not an option to just trap and breed any old mozzie – most of them won’t breed, won’t eat, and quickly die in captivity.”

The young insectary is a thriving, heavily populated success. Around 100,000 mosquitoes are bred up every week. They are then absorbed in research programs or culled to make way for the next cycle. A new generation emerges every three weeks.

The logistics of a mosquito breeding program

As well as breeding mosquitoes, insectary staff also cultivate the various malaria parasites the mosquitoes might imbibe, often sourced from rodent models. “The mosquitos and parasites have to be produced at the same time, so you have one day with the right age of mosquito and the right stage of the parasite,” Erickson explains.

The parasites are then presented to the mosquitoes within a “blood feeder” on cages with a membrane akin to a human skin to encourage them to take a bite.

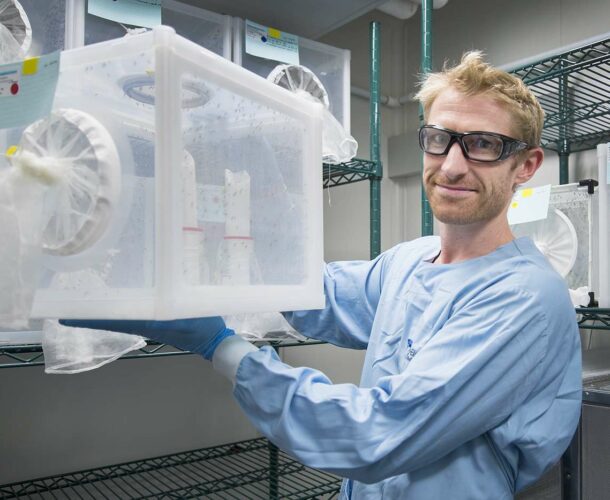

The facility is formidably secured. Inside it’s a long way from a Melbourne winter, the air in the adjoining small rooms heavy with heat and humidity and smells of the fish food fed to the larvae. In cages and trays wrapped in swathes of white netting, mosquitoes move through the stages of their short life, shuffled from tray to cage and between rooms.

Niche expertise

Sara Erickson hails from the American mid-west, farming country. And she has become a farmer of sorts, wrangling some exotic species. She breeds, manages and maintains herds of mosquitos within the high-tech fences of the Walter and Eliza Hall insectary.

So how did she get here from there?

As an undergraduate student she picked up a job as a research assistant in a mosquito research laboratory. That spun into a masters’ degree in medical entomology, studying mosquito biology at a laboratory working with mosquito-borne viruses.

This saw her venturing into the field, collecting mosquitos across the state and testing them for infections, enjoying the nexus of fieldwork, laboratory work, and the imperative of critical public health outcomes.

A focus on the human impact of parasitic infection

When it came time to pursue a PhD, Erickson switched to parasitology, so the mosquitoes stayed, but the pathogens became more varied. She zeroed in on a nematode parasite that causes human lymphatic filariasis, which manifests as elephantiasis, in which limbs or other parts of the body are grossly enlarged because the parasite worms have blocked parts of the lymphatic system.

It’s not a fatal disease, but it is a disabling, disfiguring, painful and burdensome one that affects over 120 million people around the world. Erickson obtained a grant to investigate the infection in Papua New Guinea, working in Madang on and off over three years. It was here that she first encountered malaria researchers from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“They told me their institute was expanding and building an insectary. This was 2011, and I finished my PhD and put my name forward for the job. They needed an expert to work with mosquitos and controlled exposures in the laboratory setting. They also needed a lot of safety experience, because this work would be in high containment laboratories – and that’s just what I’d done in my scientific past.”

And so it is that Erickson has come to Melbourne from Iowa via Wisconsin and Madang, to manage the institute’s $1.5m insectary.

An integrated research facility

There are other insectaries attached to research centres in Australia, “but the unique thing we have here are the malaria experts, and increasingly they are coming into the insectary to learn more about handling mosquitoes and begin exciting new research endeavors”.

Erickson hadn’t heard of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute until she encountered its people in Madang, but was quickly impressed by the caliber of its impacts over 30 years of work on malaria. While her own research ambitions have been put on hold to develop and manage the facility, she hopes that as more projects harness its potential, she will become part of an expanded malaria program involving the institute and other Australian researchers.

“I expect great things now that we have this new resource for our researchers to work with.”