As the institute’s focus turned to immunology, there were many mysteries to be answered about how the immune system responds to viruses and bacteria.

A new partnership

Dr Gordon Leslie Ada, who has made important discoveries about flu viruses at the institute, is intrigued by how foreign proteins actually induce immune responses – where they go after injection, and how they find and react with immune cells.

He enlists Sir Gustav Nossal to work with him. Nossal has a powerful antigen (foreign protein) derived from the ‘flippers’ of bacteria, which elicits a strong antibody response.

Nossal later recalls: I grabbed at the chance of working with Gordon and the result was a harmonious, productive five-year collaboration.”1

Tracing antigen fate

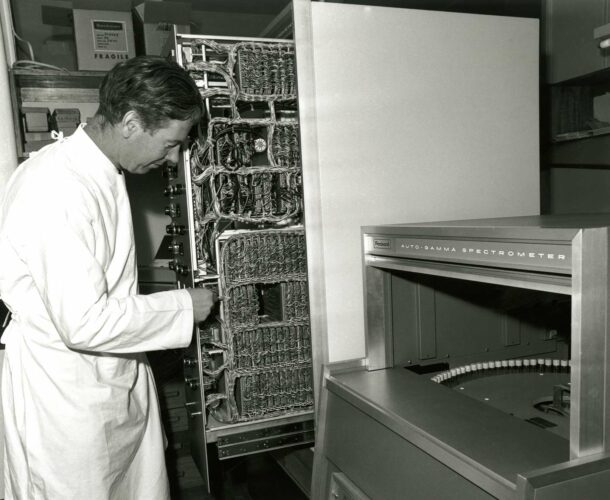

Nossal and Ada use their expertise to develop a way of tagging and tracing the movement of a powerful antigen called flagellin in the body using radioactive isotopes.

“Together we could figure out to which tissue the flagellin went, what biochemical compartments of cells were involved, and, most critically, where at the microscopic level the flagellin was located… giving a dynamic picture of the fate of antigen as the immune response evolved.”

“The very first, tentative, highly imperfect experiment already yielded an unexpected result that I realised, intuitively and immediately, must be important.

“Discrete, circular blotches of silver grains were visible over the superficial portions of the lymph nodes… the apparently spherical deposits of antigen were something new.”1

Developing and refining new technologies with typical prowess from their support staff enables the team to precisely reveal the antigen’s fate.

“The antigen was held not inside scavenger cells but rather on the surface of a new kind of cell, the follicular dendritic cell or FDC. These antigen-capturing cells had long, thin, twisting branches or dendrites which had the capacity to hold antigen on their surface for long periods of time.”1

A love affair begins

It was here – in what was known as the germinal centre – that the antigen network meets with B cells, the antibody producers, to elicit an immune response.

“It looked as though the antigen depot had attracted the ‘right’ kind of B cells and had stimulated them to divide repeatedly,” Nossal later recalled.

The discovery explains how follicular dendritic cells are essential for long-lived immunity, and are the key to successful vaccines, driving the creation of immune ‘memory’ which will become the focus of research at the institute for decades to come.

It was also the beginning of Nossal’s “30-year love affair with immunological memory and germinal centres”.1