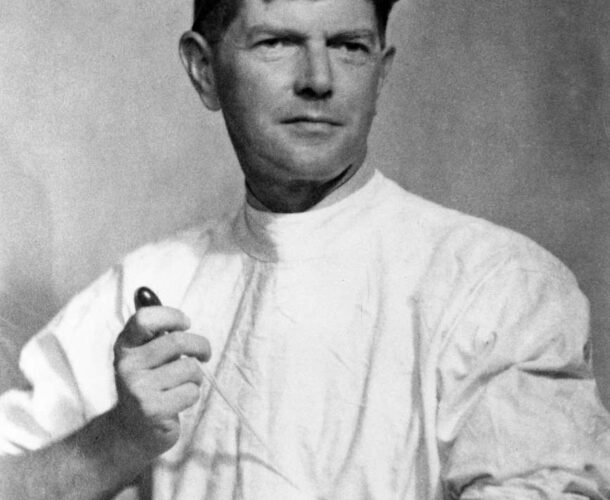

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet begins his research career at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

With major contributions in bacteriology, virology and immunology, a Nobel Prize and multiple knighthoods, Burnet becomes one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century.

At a time when most talented young Australian scientists left for international positions, Burnet remained in Australia, playing a pivotal role in helping to build the field of medical research in this country.

The path to research

As a medical graduate, it became clear that while Burnet’s skills as a physician were exemplary, he lacked empathy. He was initially nonplussed to be offered a post as pathological registrar at the seven-year-old Walter and Eliza Hall Institute rather than a clinical position at the Melbourne Hospital. But “on thinking it over I’m sure it’s a chance not to be missed,” he wrote in the diary he shared with biographer Christopher Sexton. “Though I am an excellent hospital physician I am by no means likely to be a success as a GP. On the other hand, I believe strongly in my suitability for laboratory and research work and there are bound to be further opportunities for a well-trained research pathologist.”1

In March 1923, soon after joining the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, where he would remain for much of the next 40 years, he wrote that “the fever of scientific research is beginning to grip me.

“All our work, even the most routine investigation of sputum and urine, is research … It is all a quest for knowledge, knowledge that minds have not yet assimilated, experimental facts to be observed and the widest interference to be drawn from them.”

The influence of Kellaway

In 1923 Professor Charles Kellaway was appointed director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, bringing the experience, vision and determination to lift the fledgling facility into the ranks of the world’s finest. He identified Burnet as a potential leader in bacteriology and encouraged him to gain skills overseas, dispatching him to London’s Lister Institute for two years.

Burnet returned to Melbourne and embarked on the first, defining and spectacular phase of his long career as a virologist, distinguishing himself as “a most unusual microbe hunter”, in the words of his scientific apprentice and administrative successor, Sir Gustav Nossal. By the time he was elected to the Royal Society in 1942, he was among the world’s most distinguished virologists.

In 1944 he became the third director of the institute.

Burnet’s contributions to immunology

Burnet had long nurtured a deep interest in immunology. “Two specific questions concerned him most,” Nossal has observed. “How does the immune system distinguish self from non-self? How can one animal make such a vast array of specific antibodies, all different? This speculative work led to the prediction of the phenomenon of immunological tolerance in 1949 (and thus to the Nobel Prize) and the articulation of the clonal selection theory of antibody formation in 1957”. It reverberates still through modern immunology.

Burnet’s breakthrough theory about how the immune system really worked developed earlier ideas by a Danish scientist, Niels Jerne, “which started the train of thought”, says Nossal. In science, “we all stand on the shoulders of giants.

“As Jerne said at Burnet’s retirement symposium, ‘I hit the nail, but you hit the nail on the head’. Burnet’s essay on clonal selection theory became one of the most successful papers ever written. Everything that was in it turned to gold.”

Burnet considered this the most important work of his career, despite the 1960 Nobel recognising earlier work. Nonetheless it was a validation he had “ardently craved”, says Nossal.

“It was absolutely clear to me that this rather stern, rather aloof, forbidding person mellowed most drastically after his Nobel Prize, and he became a companionable kind of person. This was what he felt was the vindication of his life’s work.”

1 Sexton C (1999) The Seeds of Time, The Life of Sir Macfarlane Burnet, South Melbourne, Oxford University Press.