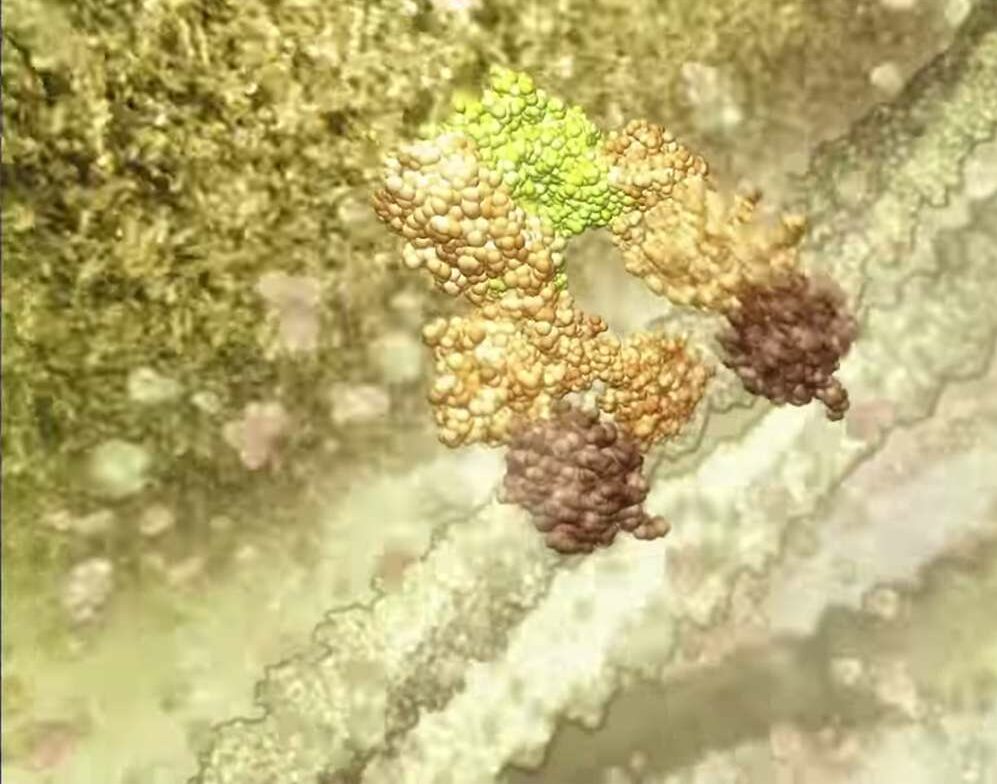

Initial studies of BH3-mimetics, agents that block the pro-survival BCL-2 family of proteins, are shown to selectively target cancer cells and induce them to undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis).

The agents are being co-developed for clinical use by biotechnology companies AbbVie and Genentech, a member of the Roche group, and were discovered in a joint research collaboration that involved Walter and Eliza Hall Institute scientists.

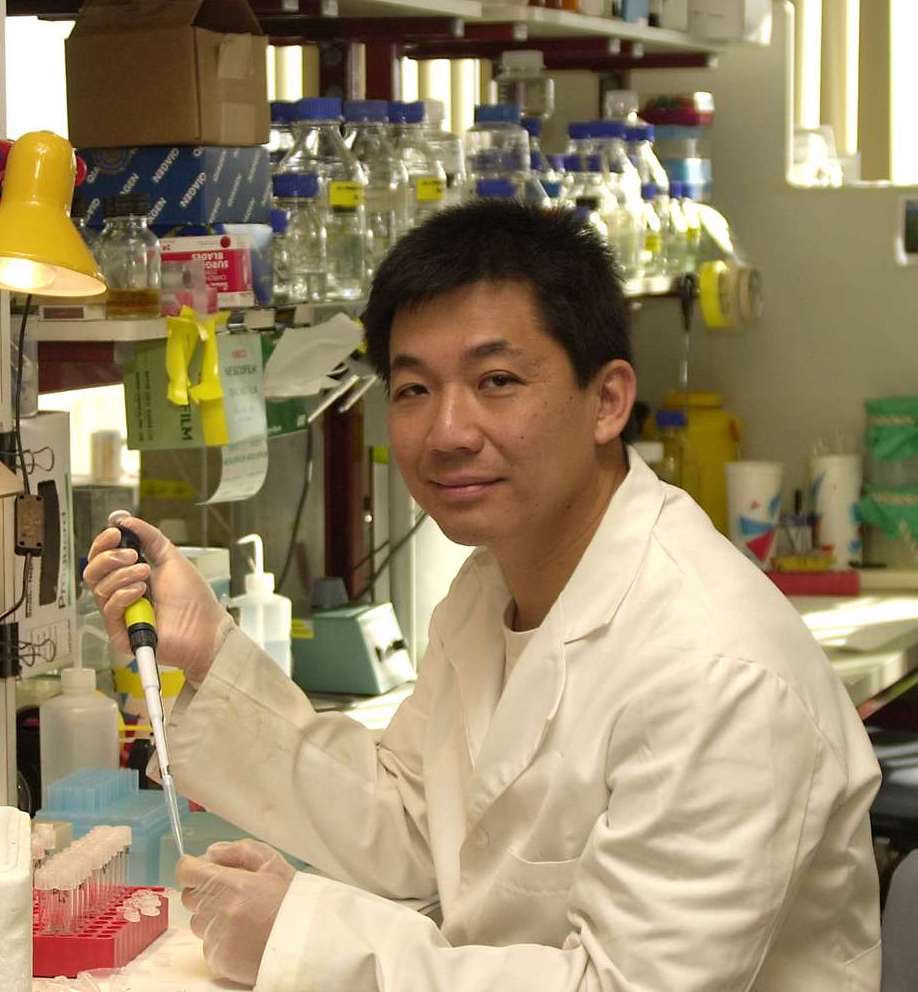

The research requires a large team of talent, and includes Professor David Huang, Professor Jerry Adams, Professor Andrew Roberts and PhD student Kylie Mason.

Mason describes how she ended up researching leukaemia at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

A defining moment

At 15, Kylie Mason was a determined student. She fancied a career in forensic detective work, but was rather deflated to discover that the Australian coronial system didn’t bear much resemblance to the one Quincy M.E prosecuted on television reruns.

Then she started to struggle at school. She was so tired she had to give up her gymnastics, which she had pushed to a promising level. She was covered in inexplicable bruising. Finally she collapsed on the Balwyn High School running track. Within days she was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

The good news was that in 1988 there were successful treatment regimes for childhood leukaemia, with some of the key breakthroughs having been achieved through the pioneering clinical work of Dr John Colebatch at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital. Only 20 years earlier the same diagnosis would have been considered fatal.

A life of fighting cancer

The bad news was “that my age was against me,” Mason recalls. “The older you are when you get childhood leukaemia, the worse it is. I was given a 50/50 chance.”

One day, when she was feeling a bit bleak, one of her specialists at The Royal Melbourne Hospital asked if she would like to go down to the laboratory and take a look at her leukaemia cells under the microscope. “I found that really therapeutic – to see the enemy. That’s what I’m getting rid of.”

It was a defining moment, putting her on course to pursue a different kind of medical detective work, focused on assisting the living rather than examining the dead.

Today Dr Kylie Mason is a haematologist and cancer researcher, splitting her time between bedside work with patients at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and bench work in her laboratory at the University of Melbourne.

Until 2013 her scientific work was at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, where she obtained her PhD working with Professor Andrew Roberts and Professor David Huang.

The role of physician/scientist is a challenging one. “It’s hard to find the balance. The clinical work pulls you. The patients are there, and their needs demand immediate attention – you can’t ignore someone who is unwell, but you might ignore that grant application or the bench work if it takes another day, then that becomes a week, or a month.

“But I’ve always been conscious that I had benefited so much from medical research – this was a way to pay it forward. As a doctor you can make a huge difference to individual patients, but with research you can make a difference on a much larger scale.”

Getting the best out of new drugs

Mason had the opportunity to make a profound difference as a consequence of her part in the institute’s landmark investigation into the processes of cell death and survival. The failure of some cells to die, or of cells dying when they shouldn’t, can lead to diseases including some cancers.

In 2006, while pursuing her PhD, she was part of a team evaluating a new class of cancer drugs developed by Abbott Laboratories (now AbbVie). The drugs induce cell death by blocking other proteins that promote cell survival. Mason published a paper that identified a weakness in the potential of the drug (called ABT-263), and suggested how combination therapies with other drugs might overcome that limitation. After publishing the widely-cited paper she went on to identify effective combined therapies in mouse studies.

Saving platelets

She also burrowed into some concerns about the implications of the drug on platelet biology. “That was a fortuitous discovery. With my colleagues we discovered the protein that tells the platelets when to live and die. It solved a conundrum of 40-plus years, and was critical because in the drugs we were dealing with had risks for a low platelet count and bleeding.”

Such side-effects had the potential to derail the drug’s development had they not been understood. Instead the research findings were used to develop a stringent dosing regmien to overcome them.

Following this work, Genentech and Abbott (now AbbVie) decided to join forces with each other and institute scientists to develop a new drug, venetoclax, which more specifically targets BCL-2. Venetoclax progressed into promising clinical trials and eventually to approval for use in Australia, the United States and European Union.

It’s been, Mason admits, a tough road. Stepping out of a clinical career to go back to student life and start over, forfeiting income and the support of familiar hospital systems and protocols, was often deeply challenging.

In recent years she also had to deal with a benign brain tumour and other likely side-effects of the lifesaving treatment she received as a teenager. She worries about the health implications on her own children. But these concerns motivate her to keep working to refine the treatments and side effects on offer to patients.

“Hopefully this next group of kids coming through treatment won’t have the same problems,” she says.

Supportive research

In 2013 Mason took up a scholarship to continue her scientific work at The University of Melbourne, though she remains involved with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute through the BH3-mimetics trials.

“It’s interesting having left the institute, you come to appreciate just how much it offers. The philosophy of allowing researchers to get on with the research by providing what they need – not just nice labs and a desk but experienced animal technicians, all that supportive structure around the core work. That’s the core philosophy that supports such stellar research.”