“It is difficult to express how grievous is her loss to the institute. She was the most outstandingly competent bacteriologist with whom I have ever worked… Our own sense of loss gives us a measure of the sympathy due to her family in their bereavement.” Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet

A short and brilliant career

During World War II, scrub typhus was as deadly as gunfire for soldiers in tropical climates. Having first-hand experience of the effects of war – Dora Lush spent part of the blitz in London — and with two brothers in the Australian armed forces, the young bacteriologist had more reason than most to devote herself to finding a vaccine that could prevent the disease carried by microbes in scrubby vegetation. Little did Dora think that she would eventually succumb to the disease herself.

Giving her life to science

Dora Lush is two months shy of her 33rd birthday when she dies in May 1943, she has achieved a great deal in her lifetime.

Dora has been a trail blazer for other young women. She completed physics and chemistry in her final school years at a time when this was uncommon; and won a scholarship to the University of Melbourne where she studied science, gaining first a bachelor degree then a Master of Science. Dora was then appointed a bacteriological research fellow, in 1934, at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

At the institute, Dora works closely with the assistant director Professor Frank Macfarlane Burnet examining viruses and the human immune system. When she leaves for London in 1939, she has co-authored with Burnet at least 10 journal articles, detailing their work on influenza, myxomatosis and the herpes simplex virus.

Outstanding in her work and social pursuits

Keen to extend her experience, Dora travelled to London and worked at the National Institute of Medical Research, where she was lauded as doing “outstanding work” as well as being a “popular and cheerful colleague” who, according to an obituary in The Lancet, “seemed to enjoy the blitz”. No doubt this referred to her willingness to give most things a go, both socially and professionally. Australian newspaper records show her as a glamorous debutante in 1929, vice-captain of the university basketball team, and later on the ski slopes at Mt Hotham and attending numerous balls and social events.

In 1942, Dora returns to the institute, bringing with her work she has begun in London on scrub typhus. Burnet is pleased to have her back and describes her as “the most outstandingly competent” bacteriologist he has worked with.

Hailed a martyr to science

Although it would later be found that antibiotics could effectively treat the disease, making a vaccine unnecessary, in the early 1940s it was assumed that the scrub microbe could only be controlled by vaccination. Developing this required ensuring the survival of the microbe by injecting it into the bloodstream of animals. This is Dora’s death sentence.

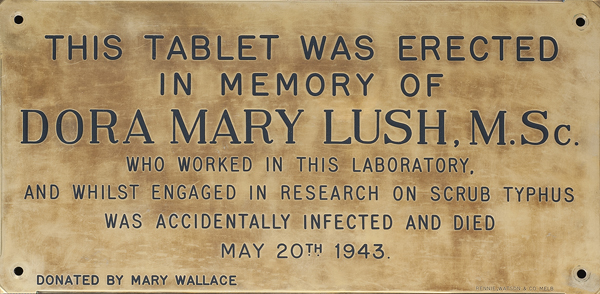

In 1943, while inoculating a mouse, she accidentally pricks her own finger. Three weeks later the disease claims her life but not before, at her insistence, she has regular blood samples taken to further research by her colleagues.

No wonder she captured the public imagination and, according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography was “hailed as a martyr to science and the war effort”.

Academic recognition

To this day, the National Health and Medical Research Council recognises Dora Lush’s skill and the importance of her work by awarding Biomedical (Dora Lush) Postgraduate Research Scholarships to outstanding students.