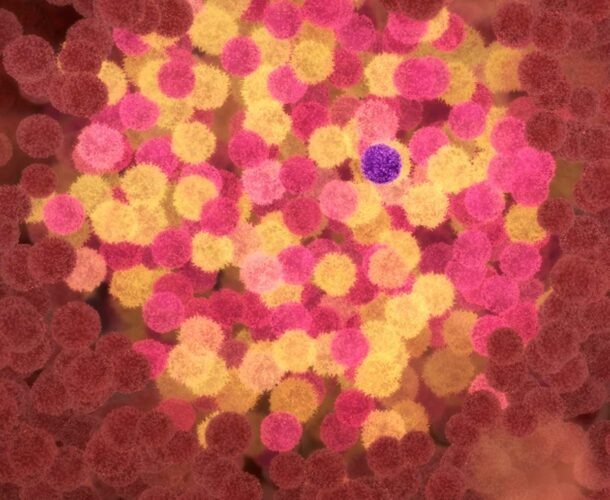

In 1991, CSFs are approved for use as a supportive therapy for cancer patients, the culmination of 25 years work. CSFs boost infection-fighting white blood cells after chemotherapy and help to collect blood stem cells for bone marrow transplants. CSFs are now used to treat patients with a variety of cancers – including leukaemia, lymphoma, breast cancer and lung cancer, in stem cell transplants and for other blood disorders, such as neutropenia.

Professor Donald Metcalf, who led the CSFs program at the institute, later wrote:

“That the CSFs were able to make such a rapid impact in the clinic owes much to the enterprise of three medical graduates who each served their apprenticeship in the unit… George Morstyn, Graham Lieshcke and Glenn Begley. Each was to play a crucial role in ensuring the clinical use of CSFs in the management of cancer patients.”1

Witnessing a revolution in cancer care

Dr George Morstyn was one of the clinician-scientists who led the clinical trials of CSFs in Melbourne, Australia, and witnessed a revolution in cancer care.

In 1978 Time magazine published an article about an American cancer researcher named Sydney E Salmon. “Salmon had shown you could take tumours from patients and grow them in Petri dishes,” recalls Morstyn.

“His idea was that you could use these to test different chemotherapy drugs and select which tumour would respond to which drug.” A fabulous prospect that still hasn’t been fully realised, but it excited the then 28-year-old Monash graduate and Alfred Hospital resident. “At the time metastatic cancer treatment was a bit like wandering around in a dark room, hoping you’d bump into what you were looking for.”

He showed the article to Monash’s Professor Barry Firkin and inquired whether anyone in Australia was doing similar work. Not really, Firkin said, but “there is this guy Don Metcalf on the other side of the river, and he grows blood cells. Why don’t you go and see him?”

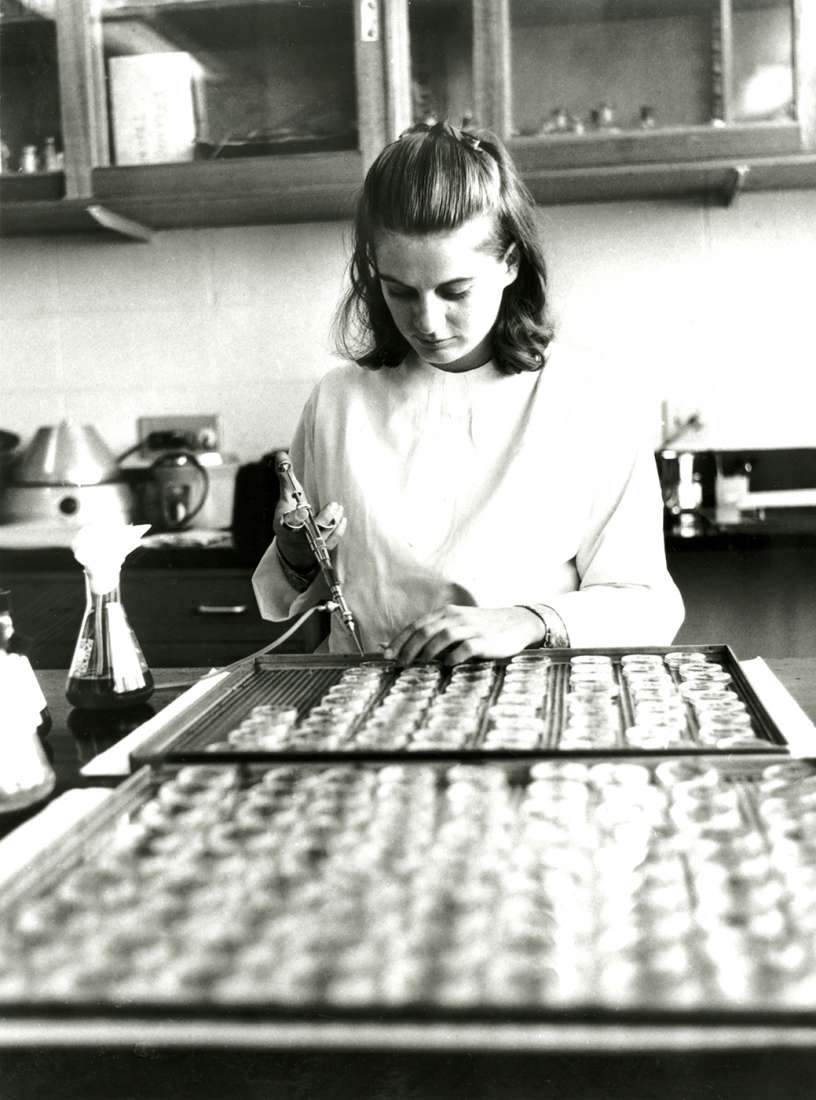

Morstyn presented himself to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute’s Professor Don Metcalf and asked if he might do a PhD. He was promptly assigned a bench in a corridor where he spent the spent the next two years growing cultures from human samples.

Purifying CSFs: still frustratingly distant

By then Metcalf was deep into the task of trying to purify the elusive one-molecule-in-a-million colony stimulating factors (CSFs) that he and colleague Dr Ray Bradley had discovered back in 1965. This magic agent had the power to yield abundant crops of bone marrow cells and hence white blood cells. Its potential to revolutionise treatment of patients with low counts of white blood cells and little capacity to fight infections was profound, but still frustratingly distant. Metcalf’s team had yet to collect a single vial of pure CSFs.

“You’d come in the morning and you would know he was there because you could smell the cigar,” recalls Morstyn. “He spent his whole day sitting there at the microscope counting colonies, which was what I was doing too.”

Morstyn joined the lab in 1979 and investigated the purification and identification of human progenitor cells, which like a stem cell might differentiate into a particular type of cell, but within a narrower range. Meanwhile Tony Burgess, Nick Nicola and others developed multistep purification techniques for the CSFs.

Clinical trials of the “miraculous” drug

As the Metcalf team continued its efforts, Morstyn went to the US to train as an oncologist at the National Cancer Institute, learning how to conduct clinical trials. He returned to Australia after he was recruited by Burgess to Melbourne’s Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research that had grown out of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, and collaborating with the institute on the CSFs to lead the clinical program.

Again he was in the right place, at the right time, and with perfect credentials to be part of the next phase of the CSFs story. Melbourne was to host clinical trials of two emerging CSF drugs, and Morstyn was appointed principal investigator.

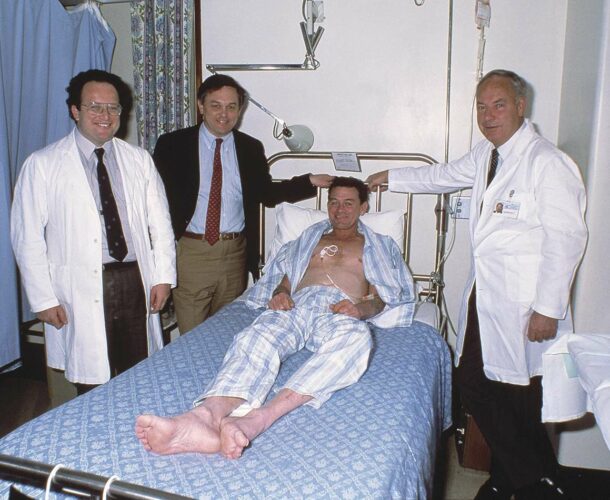

From the outset the effects of the drugs on cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy was startling. “You could see from the first patient treated that white cell counts were going up. Patients felt better. They didn’t have infections. They stayed out of hospital.

“It was sort of miraculous because even at the lowest doses you could see changes in the white blood cells.”

By boosting their immune systems, CSFs could fortify patients to survive the ravages of chemotherapy. Today more than 20 million cancer patients have been treated with CSFs, which turned out to have more benefits than were ever imagined.

More benefits that ever imagined

One of the CSFs drugs, Neupogen – developed by US company Amgen – was found to increase the number of stem cells circulating in the blood. These cells can become any type of cell in the body, and hence have potent healing potential. When patients who would ordinarily require bone marrow transplants were transfused with these stem cells – sometimes their own, sometimes from a donor – they quickly began to recover. This revolutionised the field of bone marrow transplantation.

One of the early beneficiaries was George Morstyn’s brother, Ron, who was diagnosed with myeloproliferative disease, requiring a marrow transplant from a matched unrelated donor. The donor – in the Netherlands – was given Neupogen to yield stem cells, which were then flown to Ron Morstyn’s Sydney bedside.

Neupogen was also effective in treating children with severe chronic neutropenia, and who otherwise were condemned to a life of multiple infections and an early death.

Invigorated by his part in the testing of the CSF drugs, Morstyn took what was then, in 1991, an unusual career step, venturing into the fledgling biotechnology field as an advisor to Amgen. He remained with the company until 2002, working on more than 10 other drugs and rising to the role of senior vice president of development, responsible for 1400 staff.

A “lucky” experience

“I was very lucky. I had worked at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute on the biology of CSFs. Then I worked on the very first clinical trials. At Amgen I was able to help get the drugs approved and extend their uses. I’d gone from treating people one-to-one to being responsible for them in the millions.”

Many times in those years he found himself reflecting on – and grateful for – his formative experiences at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“What I learned there were values. To just do everything right, no cheating, no bullshit.” Engaging with corporate and institutional science on the world stage. “That’s something I have taken with me through my whole career.”