When Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet took the helm of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in 1944, he had some strong ideas about the direction he wanted to take the research.

Among his priorities, as recalled by his biographer Christopher Sexton1, was to establish a facility for clinical research within the institute – this is despite the fact of his “widely known disdain for clinical science”. By 1946 he formed the Clinical Research Unit to draw the institute and the adjoining Royal Melbourne Hospital closer together, and put Sir Ian Jeffreys Wood at the helm.

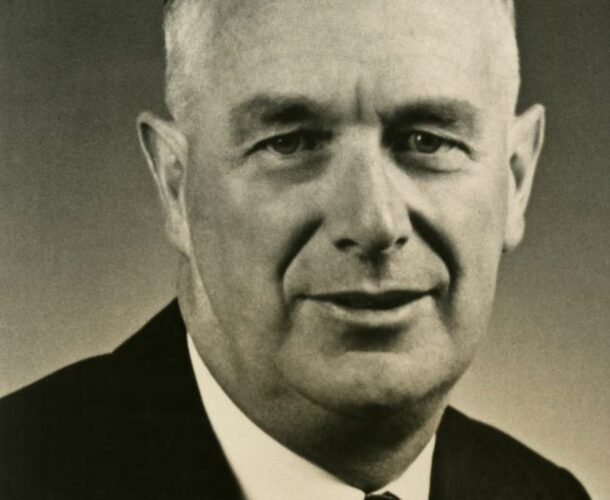

Ian Wood, an interest in obtaining, storing and managing blood

Burnet already had a high regard for Wood, the son of an East Melbourne doctor who had studied medicine at the University of Melbourne a few years after Burnet. In 1930, when Wood was a resident at the (later Royal) Children’s Hospital, they had worked together on bacillary dysentery in infants. After a couple of years working in London Wood had, from 1935, held a clinical research role straddling the Royal Melbourne Hospital and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute until the war.

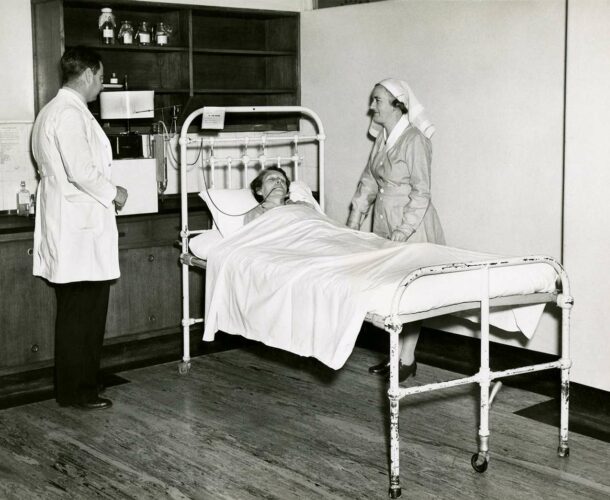

Wood’s chief clinical concern was gastroenterology and his research interest – as a means to better treatment of intestinal emergencies like hemorrhage – was in blood analysis, and in obtaining, storing and managing blood, which was being increasingly used for transfusions.

War, the impetus for a blood bank

The outbreak of the Spanish civil war in 1936 had created what Burnet characterised, in his 1971 history of the institute2, as “a laboratory model for Armageddon. British volunteer medical groups were active in providing blood transfusion for the wounded and all around the world service medical personnel were assessing the difficulties and benefits of the Spanish war experience”.

Wood and his institute colleagues, Fannie Williams and Dr Lucy Bryce followed these developments closely and established a blood bank in the institute. The blood bank was useful in treating hospital cases, but was “definitely oriented toward the coming war”, Burnet wrote.

As the war loomed closer the blood bank became increasingly important, and soon nearly half the institute’s space was taken over by the Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service activities. “As recruits flowed into the services, each had to have his blood group tested and recorded and in Victoria, all this ‘blood-typing’ was initially done at the institute,” Burnet wrote. By mid-1942 nearly a quarter of a million such tests for servicemen and for civilian donors had been done.

It was a massive logistical exercise founded on the work of Wood and his institute colleagues who raced to develop protocols and blood transfusion panniers (kits), which were ready in January 1940 – just in time for Wood to take them with him to the Middle East.

Wood was responsible for the Australian military’s blood storage and transfusion services, and later oversaw resuscitation and transfusion services with the field ambulances and commanded a medical division at Tobruk and later in the war spent time in New Guinea. From the Melbourne medical corps headquarters he was also part of Neil Hamilton Fairley’s critical research on malaria and the use of penicillin in the field to treat casualties.

Pioneering clinical and research work

After the war he returned to the institute as Burnet’s assistant director and the role running the Clinical Research Unit. The new unit needed its own ward at the hospital fitted out, and to that end Wood was successful in exciting Melbourne’s horse racing clubs to donate £20,000 to the cause.

Professor Richard (Rod) Andrew, founding Dean of Medicine at Monash University and also a gastroenterologist, later described Wood’s introduction of the blood bank at the institute to be one of his greatest achievements. His clinical and research work on gastroenterology was also important, especially his invention of the flexible gastric biopsy tube, which Burnet describes as being the consequence of a happy accident.

His work at the institute pioneered research on the effects of alcohol on the stomach and liver, and fostered growing interest on the social and medical effects of alcohol by other members the institute.

Burnet credited his work on autoimmune disease as feeding into the “switch” of the institute’s main theme from influenza virus to immunology. He published 70 medical and research articles, and retired from the institute in 1963.

“Ian Wood had a very special personal place at the institute that included, but transcended, the distinction of his research,” Burnet wrote. “To all of us, he was the prototype of the good doctor concerned, above everything else, with the well-being of his patients and the dignity of his profession. I, personally, owe much to his integrity, thoughtfulness and wisdom over the whole period of our association,” Burnet wrote.

Sir Ian Jeffreys Wood was a pallbearer at Burnet’s funeral in 1985.